Key Takeaways:

- Real answers don’t come from one source; they come from layers: If a firearm is genuinely obscure, no single book, website, or forum will give you the full story. Serious research means stacking sources: start with standard references to establish context, then move into factory records, institutional archives, auction documentation, and expert opinion. Each layer fills gaps the others can’t. If you rely on just one, you’re guessing.

- Documentation matters more than opinions: What turns an unusual firearm into a historically credible one is paperwork, not enthusiasm. Factory letters, archive confirmations, auction precedents, and written expert evaluations carry weight because they’re verifiable. Forums and online chatter are useful for leads, but they’re not proof. In collecting, documented facts always outlive stories.

- Obscure usually means slow, and that’s normal: Deep firearms research isn’t fast. Archives take time, experts are booked, some records are incomplete, and some answers simply don’t exist anymore. That isn’t failure, that’s the reality of limited production and regional manufacturing history. Patience isn’t just part of the process; it’s the price of doing the research correctly.

You’ve just inherited a peculiar-looking revolver from your grandfather’s estate. Or maybe you stumbled across something unusual at an estate sale, a rifle with markings you’ve never seen before, a serial number that doesn’t match anything you can find online, and a design that seems to exist somewhere between two well-known models.

Now what?

Researching obscure or limited-production firearms can feel like detective work without a clear starting point. Unlike researching a standard Colt 1911 or a Winchester Model 70, where information practically floods the internet, tracking down details about a rare variant or a short-run manufacturer requires a different approach entirely. You can’t just Google it and expect reliable answers, or worse, you’ll get conflicting information from forums where everyone’s an expert, but nobody actually knows.

Here’s the thing: researching truly obscure firearms in 2026 requires a multi-layered strategy. You need to know where the authoritative information lives, which institutions hold the keys to manufacturer records, how to read between the lines of auction catalogs, and when to call in human expertise. It’s not complicated once you understand the system, but it does require patience and knowing which resources to trust.

Let me walk you through how serious collectors and researchers actually do this work.

Start With the Big Three Reference Books

Before you go chasing down obscure archives or paying for expert appraisals, you need to establish a baseline. Even if your firearm seems impossibly rare, there’s a decent chance someone has documented it somewhere. The trick is knowing which references actually matter.

The Standard Catalog of Firearms is your first stop. The 2026 edition, the 36th, is still one of the broadest single-volume references for commercial firearms and variants. It’s enormous, it’s expensive, and yes, you need it anyway if you’re serious about this hobby.

What makes the Standard Catalog valuable isn’t just the breadth of coverage, it’s the attention to production variations. A firearm you think is unique might actually be a documented variant with known production numbers. The catalog breaks down changes by year, serial number range, and, when available, manufacturing plant. It won’t tell you everything, but it’ll tell you what’s known in the commercial firearms world.

Next up is the Blue Book of Gun Values. This one’s primarily aimed at modern firearms, but don’t discount it for historical research. The Blue Book is useful for condition language and market context, especially their Photo Percentage Grading System, and their online tools are updated regularly. You’ll see this same grading language used by dealers, appraisers, and auction houses. More importantly, it tracks market trends and rarity assessments that can help you understand whether your obscure piece is genuinely rare or just uncommon.

For antique American firearms, Flayderman’s Guide remains a cornerstone reference for identification and historical context (even though it isn’t updated every year). This isn’t light reading. Flayderman’s goes deep into maker histories, production quantities, military contracts, and regional variations. If you’re researching an obscure percussion revolver or an unusual Civil War carbine variant, this is where you’ll find details that don’t exist anywhere else in consolidated form.

I keep all three within arm’s reach of my desk. Physical copies, not digital. There’s something about being able to cross-reference quickly, flip between sections, and mark pages that makes physical books invaluable for this kind of research.

But here’s where it gets interesting. These references will get you maybe 60% of the way there on a genuinely obscure piece. They establish what’s known publicly. For the remaining 40%, you need to go deeper: the specific history of your particular firearm, the exact shipping date, the original configuration before someone modified it fifty years ago.

When Books Aren’t Enough: Institutional Archives Hold the Keys

Manufacturer records are the holy grail of firearms research. If you can document that your specific serial number left the factory on a particular date, configured in a certain way, and shipped to a specific dealer or military unit, you’ve just added significant value and historical legitimacy to the piece.

The Cody Firearms Records Office in Wyoming holds one of the most important firearms archives in existence. Their records cover Winchester, Marlin, and L.C. Smith, as well as makers such as Ithaca, Savage, and A.H. Fox. However, coverage varies by maker and model, and some records have membership or access limitations. If you’ve got an unusual Winchester variant or a Marlin with mysterious markings, Cody’s archives might hold shipping records that explain everything.

But here’s what most people don’t realize: accessing these archives isn’t always straightforward. Their stated turnaround is roughly four weeks after payment, but complex inquiries can take longer. You can’t just email them and expect a complete research report back instantly. They’re an educational institution with limited staff. Sometimes you’ll need to work with researchers who specialize in their collections, pay research fees, or even plan a visit if your inquiry is complex enough. The payoff can be enormous. I’ve seen documentation from Cody increase a firearm’s value by 40% because it proved a rare configuration, but it requires patience.

For specific manufacturers, dedicated archival services can provide what’s called a “factory letter.” These are official documents that verify a firearm’s original configuration based on the manufacturer’s own records. Colt Archive Services is probably the most well-known, and they’re meticulous. A Colt letter will tell you when your revolver left the factory, what barrel length it had, what finish, what grips, and where it shipped. For Colt collectors, a factory letter isn’t optional; it’s essential documentation for any rare Colt.

Smith & Wesson Historical Foundation provides similar services for S&W firearms. They’ve got records going back to the company’s founding, and their letters carry substantial weight in the collector community. The process is similar to Colt’s; you submit your request with serial number and any known details, pay the research fee, and wait for their historians to pull the factory records.

For Ruger firearms, the situation’s a bit different. Ruger’s online serial lookup tools are helpful for approximate ship era context and general model information, but verify which services are currently available. Ruger has periodically paused the official Letter of Authenticity service. Their “product history” tables remain available as reference material, but they’re explicitly marked as “reference only” rather than official documentation.

The catch with all these services? They’re not cheap, and they’re not fast. A Colt letter might run you $150 to $300, depending on the firearm’s age and complexity, and you’ll wait several months. But if you’re researching an obscure variant that might be worth serious money with proper documentation, it’s money well spent.

Don’t Overlook Proof Marks and Inspection Stamps

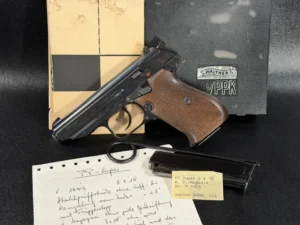

Here’s something that deserves its own mention: if you’re researching obscure firearms, especially European pieces or military contract guns, proof marks and inspection stamps are critical identifiers.

These small stampings indicate where a firearm was proofed, what standards it met, and, often, who inspected it for military acceptance. Different countries, different eras, different proof houses, each has its own marking system. A Belgian proof mark looks nothing like a German one, and British proof marks changed multiple times across different periods.

When you’re photographing an obscure firearm for research purposes, get clear, close-up shots of every proof mark, inspection stamp, and unusual marking you can find. These are often more useful for identification than the firearm’s overall appearance. Collectors who specialize in European arms or military contract pieces live and die by these markings.

And while we’re talking about photographs: if you’re going to post images online for identification help, consider cropping or obscuring at least the last few digits of the serial number. Focus your photos on markings, proof stamps, and distinctive features rather than showing the complete serial number to the entire internet. It’s a small privacy measure that’s become standard practice among serious collectors.

Auction Records Are Research Gold (If You Know How to Read Them)

Here’s something that took me years to fully appreciate: auction catalogs from high-end firearms auctions are essentially published research documents disguised as sales literature.

When Rock Island Auction Company puts together one of their Premier auctions, they run significant sales seasonally, including their recurring May Premier events; they’re not just slapping photos in a catalog and calling it done. Their research staff digs into provenance, verifies authenticity, documents variations, and often uncovers historical details that haven’t been published anywhere else. These catalogs become reference materials in their own right.

I’ve got a shelf full of old Rock Island catalogs, and I reference them constantly. Found an unusual Remington percussion revolver? There’s a decent chance Rock Island sold a similar example in the past five years, and their lot description will include production details, known variations, and comparative sales data. Even if you’re not bidding, these catalogs teach you how to evaluate and describe obscure firearms using language that serious collectors understand.

Poulin’s Antiques and Auctions runs Premier Firearms & Militaria auctions throughout the year; its Spring 2026 event is scheduled for late February and showcases truly unusual pieces. What makes Poulin’s collection valuable for research is its focus on transferable historical items with documented military provenance. If you’re researching an obscure military contract firearm or an experimental military variant, Poulin’s past sales often include similar examples with detailed historical context.

Morphy Auctions employs specialized divisions for different collecting categories, and their firearms experts are top-tier. They regularly handle essential 18th and 19th-century collections, which means their catalogs include detailed discussions of early American makers, regional gunsmiths, and manufacturing techniques that don’t appear in standard references. The photography alone is worth studying, high-resolution images that let you compare markings, finishes, and construction details.

Here’s how I actually use auction records: when I’m researching an obscure piece, I’ll search past auction results (most major houses have searchable archives online) for anything similar. Not just the same model, similar markings, similar serial number ranges, similar manufacturers. I’m looking for clues. How did the auction house describe it? What documentation did they reference? What did it sell for, and how does that compare to standard variants?

Sometimes you’ll discover that your “unique” firearm is actually a known variant that just doesn’t appear in standard references because it’s too obscure. Other times, you’ll confirm that you’ve genuinely got something unusual, and the auction records will give you comparable sales to establish value.

Understanding the Research Hierarchy

Not all sources carry equal weight. When you’re building documentation for an obscure firearm, understanding which sources matter most will save you time and prevent you from treating forum speculation as fact.

Here’s how serious researchers prioritize information:

Factory letters and original manufacturer ledgers sit at the top. These are primary sources, the actual records created when your firearm was made. Nothing beats this level of documentation.

Contemporary government contract records come next, particularly for military firearms. If you can find War Department contracts, acceptance inspection records, or military shipping documents from the period, you’ve got gold-standard documentation.

Period catalogs and manuals are incredibly valuable because they show what the manufacturer was actually advertising and how they described their own products. These often reveal variations and options that aren’t documented anywhere else.

Auction catalogs from top-tier houses rank surprisingly high because their research departments employ experts and verify information before publishing. A detailed lot description from Rock Island or Morphy requires serious research.

Secondary reference books like the Standard Catalog, Blue Book, and Flayderman’s are essential starting points, but they’re compilations of information rather than primary sources. Use them to establish baselines and identify leads.

Forums and online communities sit at the bottom for a reason. They’re excellent for generating leads and initial identifications, but always verify anything you learn against higher-tier sources. Forum members can be knowledgeable and helpful, but they can also be confidently wrong.

This hierarchy matters because when you’re documenting provenance or establishing value, you need to cite your sources. “I found it on a forum” carries zero weight with serious collectors or appraisers. “Factory letter from Colt Archive Services dated 2026” is documentation that adds real value.

The Human Element: When You Need Expert Eyes

All the books and archives in the world can’t replace human expertise when you’re dealing with truly obscure firearms. Sometimes you need someone who’s spent forty years studying a particular manufacturer or military contract to look at your piece and say, “Oh, that’s one of the experimental variants from 1892, only made about fifty of those.”

Specialized collector forums are more valuable than most people realize. Reddit has active communities for collecting firearms and niche forums dedicated to specific manufacturers or eras. The key is knowing which forums have serious, knowledgeable members versus which ones are full of enthusiastic amateurs passing along folklore.

I’m cautious about forum advice; always verify anything you learn against authoritative sources, but forums are excellent for crowdsourcing initial identification. Post clear photos of markings, serial numbers (with appropriate privacy measures), and unusual features, and you’ll often get five or six responses from collectors who recognize what you’ve got. Even if they’re not 100% accurate, they’ll point you toward research directions you might not have considered.

For anything genuinely valuable or historically significant, though, you want a certified firearms appraiser or historian. These are professionals who’ve often spent decades specializing in particular areas. They’ll charge for their time, expect $150 to $500 for a detailed evaluation and written opinion, but they can provide expert insights that general databases simply lack.

A good appraiser will examine the firearm in person when possible, compare it with known examples, verify markings against manufacturer records, and provide a written assessment documenting their findings. This documentation becomes part of your provenance file, adding legitimacy and value to the piece.

One thing worth mentioning: you might have heard about using ATF tracing to research a firearm’s history. Here’s the reality, ATF tracing is a law enforcement tool tied to criminal investigations; private collectors generally can’t request a trace. The National Tracing Center only provides tracing services to law enforcement agencies conducting bona fide criminal investigations. For provenance work, you’ll need to rely on factory letters, documented chain of custody, auction records, and reputable historians or appraisers instead.

Building Your Research Strategy: Where to Actually Start

Okay, so you’ve got an obscure firearm, and you want answers. Here’s my actual process, step by step.

Start broad, then narrow. Begin with the Standard Catalog of Firearms and the Blue Book. See if your piece appears in any form. Even if it’s not an exact match, find similar models and note the production dates, variations, and known facts. This establishes your baseline.

Identify the gaps. What can’t you find in standard references? Is it the specific variant? The markings? The serial number range? The original configuration? Knowing what’s missing tells you where to focus your deeper research.

Document every marking. Before you go further, photograph every proof mark, inspection stamp, serial number, and unusual marking. Get clear, close-up shots from multiple angles. These photos will be essential for any expert consultation or archive research.

Check auction records next. Search Rock Island, Morphy, Poulin’s, and other major auction houses for anything similar. Read lot descriptions carefully. Look at the photographs. See how experts describe similar firearms and what documentation they reference.

If you’ve got a major manufacturer—Colt, Winchester, Smith & Wesson, Marlin, get a factory letter or contact the appropriate archive. This is especially important if you suspect you’ve got a rare variant or original configuration. The cost and wait time are worth it for the documentation you’ll receive.

Join relevant forums and post inquiries. Be specific, include good photos (with privacy considerations), and be patient. The experts you want to reach might only check in once a week. Follow any leads they provide, but verify everything against authoritative sources using that research hierarchy we discussed.

Consider a professional appraisal if the piece seems significant. If your research suggests you’ve got something genuinely rare or valuable, spending a few hundred dollars for expert evaluation is cheap insurance against misidentification or missed details.

Document everything you learn. Save copies of factory letters, auction records, forum discussions, appraiser reports, everything. This documentation becomes part of the firearm’s provenance and adds value if you ever sell.

The Reality of Research: Patience and Dead Ends

Let me be honest: sometimes you won’t find all the answers. I’ve got a percussion pistol in my collection that I’ve been researching on and off for eight years. I know it’s American, probably 1840s-1850s, likely a regional maker. But I cannot definitively identify the maker despite consulting every reference I own, sending photos to multiple experts, and even visiting the Cody archives.

That’s part of the appeal, though. The mystery. The ongoing search. The moment when a new piece of information suddenly makes everything click into place.

Not every obscure firearm has a Hollywood ending where you discover it’s worth ten times what you thought. Most of the time, obscure means obscure for a reason: limited production, a minor manufacturer, or a regional variant that nobody bothered to document thoroughly. The research itself becomes the reward, a deeper understanding of manufacturing history and American craftsmanship.

But when you do crack the code on a genuinely mysterious piece, when you finally connect all the dots between manufacturer records, auction precedents, and expert analysis, that’s an incredible feeling. You’ve added to the historical record. You’ve documented something that might have been lost to time. And you’ve built a provenance file that makes your firearm significantly more valuable to the next generation of collectors.

Tools Worth Having in Your Research Arsenal

Before we wrap up, let me give you a quick-reference list of resources that belong in every serious researcher’s toolkit:

Essential Books:

- Standard Catalog of Firearms (current edition)

- Blue Book of Gun Values (print and online access)

- Flayderman’s Guide to Antique American Firearms

Key Archives & Services:

- Cody Firearms Records Office (Winchester, Marlin, L.C. Smith, Ithaca, Savage, A.H. Fox—coverage varies)

- Colt Archive Services

- Smith & Wesson Historical Foundation

- Ruger serial lookup and product history (verify current service availability)

Auction House Archives:

- Rock Island Auction Company

- Morphy Auctions

- Poulin’s Antiques and Auctions

Professional Resources:

- Certified firearms appraisers (find through professional organizations)

- Specialized collector forums (verify advice against multiple sources)

- Museum curators and historians (for academic research)

Final Thoughts: Research as an Ongoing Journey

The best way to research obscure firearms isn’t a single method; it’s a combination of authoritative references, institutional archives, auction records for market analysis, and human expertise. You layer these approaches, cross-reference findings, and build documentation that tells the complete story of your firearm.

It takes time. It costs money. It requires patience when archives are slow or when experts are booked months out. But the depth of knowledge you gain, the connections you make with other serious collectors, and the satisfaction of solving historical mysteries make it worthwhile.

And honestly? The research often becomes more interesting than the firearms themselves. You start investigating an obscure revolver and end up learning about a forgotten manufacturer, a specific military contract, or a brief period when a major company experimented with designs that never made it to mass production. You’re not just collecting firearms, you’re preserving and documenting manufacturing history.

So the next time you’re holding something unusual, something that doesn’t quite match the standard references, something that makes you wonder “what exactly am I looking at?”, now you know where to start digging. The answers are out there, scattered across reference books, institutional archives, auction records, and the collective knowledge of expert researchers. Your job is simply to connect the dots, document what you find, and add your piece to the larger historical puzzle.

That’s how the best research gets done, not through shortcuts or quick Google searches, but through systematic investigation using the right resources in the right order. Start broad, narrow your focus, verify everything against reliable sources, and document thoroughly. The firearms you’re researching deserve that level of care; they’re physical artifacts of manufacturing history, each one with a story waiting to be told.

Now get to work. Those mysteries won’t solve themselves.

Frequently Asked Questions

Rarity isn’t about how little you can find online; it’s about production context. A firearm is genuinely rare when low production numbers, short manufacturing windows, experimental features, or documented special orders can be proven through records, not assumptions. Many firearms feel rare simply because they were regional, unpopular, or poorly marketed. Research separates scarcity from obscurity.

Slow down and document what you have. Photograph markings, proof marks, serial numbers (partially obscured), construction details, and finishes. Then start broad with established reference books before chasing theories. Guessing early usually sends people in the wrong direction and wastes time later.

If the firearm is from a manufacturer with surviving records, yes. A factory letter is primary-source documentation. It confirms what the firearm was when it left the factory, not what it became after decades of modifications. For collectible pieces, that difference matters. For rare configurations, a letter can be the single most important document tied to the gun.

That’s common, especially with small makers or short-lived companies. When factory records are gone, research shifts to secondary primary sources: period catalogs, military procurement records, contemporary newspaper mentions, auction precedents, and expert comparison with known examples. You may never get a perfect answer, but you can still build a credible historical case.