Key Takeaways:

- Collect around engineering, not nostalgia. A handgun collection built on mechanical “firsts” tells a story that random accumulation never will. Target the pieces that debuted specific mechanisms, from Colt’s automatic cylinder indexing to the Glock’s striker-fired polymer frame, and you’ll end up with a physical timeline of two centuries of problem-solving.

- Originality beats cosmetics every time. A matching-numbers Luger with honest wear is worth more to this kind of collection than a refinished showpiece with mismatched internals. If the goal is preserving a snapshot of a specific era’s engineering, the guts matter more than the finish.

- Document the “why,” not just the “what.” Writing down the mechanical significance of each piece turns a pile of metal into a coherent narrative. When you can explain how the toggle-lock gave way to short recoil, and short recoil gave way to polymer strikers, you’re not just showing off guns. You’re walking someone through the history of an idea.

Most handgun collections start with sentiment. But if you want a collection that actually tells a story, one that traces the arc of human ingenuity through steel and spring and polymer, you’ve got to think differently. Maybe your grandfather carried a particular revolver, or you shot a .45 for the first time and got hooked on the kick. There’s nothing wrong with collecting around nostalgia. But collecting around engineering is a different game entirely.

This approach works whether you’re building your first serious collection or refining an advanced one. Every handgun ever made is a design response, a designer’s answer to a question like, “How do we fire faster?” or “Can we make this lighter without losing reliability?” When you start seeing firearms through that lens, a collection stops being a display case full of cool guns and becomes a physical timeline of problem-solving. And honestly, that’s way more interesting.

So let’s walk through how to do this right.

Start With the Questions, Not the Guns

Before you buy a single piece, sit down and think about what mechanical problems handgun designers have tried to solve over the past two centuries. Forget brand loyalty for a second. Forget caliber debates (I know, I know). Focus on the mechanisms themselves.

You’re looking for engineering “tipping points,” the moments when someone figured out a new way to make a handgun work. These are the pieces that changed everything downstream. Every modern pistol you can buy today owes something to a handful of these breakthroughs, and your job as a collector is to find the guns that represent them.

Think of it like collecting the first edition of every book that launched a literary genre. You’re not just buying old stuff. You’re buying proof of a new idea.

The Mechanical “Firsts” That Belong in Every Innovation Collection

These form the backbone of any serious collection built around engineering leaps.

The Revolving Cylinder. You can’t talk about handgun mechanics without starting here. The Colt 1860 Army represents the mature expression of Colt’s revolving-cylinder system, first commercialized with the Paterson revolvers following Samuel Colt’s 1836 patent, then scaled up for military use with the Walker in 1847. The core concept sounds almost absurdly simple now: a rotating cylinder that automatically indexes multiple chambers in front of a single barrel.

Before practical revolvers, most handguns were single-shot, though multi-barrel pepperboxes offered limited repeating fire without Colt’s automatic indexing system. That indexing mechanism changed the math of personal defense forever. Getting your hands on a Colt 1860 in decent shape is not cheap, but it’s the cornerstone piece. If you can find one with intact original internals, you’re holding an engineering solution that echoed for over a century.

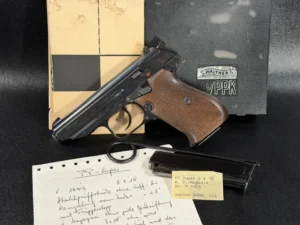

The Toggle-Lock Mechanism. This is where things get beautiful, in a strange, almost sculptural way. The toggle-lock system evolved from Hugo Borchardt’s earlier C-93 pistol, which Georg Luger refined into a more ergonomic and reliable military sidearm: the P08, adopted by the German military in 1908. The toggle joint locks straight under recoil and must hinge upward to unlock, using leverage rather than tilting-barrel geometry. It’s one of those designs that you stare at and think, “Someone actually figured this out?”

It worked, but it was finicky, sensitive to dirt and tight tolerances. That fragility is part of the story. The P08 tells you where designers were reaching, even if the destination wasn’t quite perfected yet.

The Short Recoil, Tilting-Barrel System. John Moses Browning might be the most consequential firearms designer who ever lived, and the Colt 1911 is his magnum opus. (There’s an argument for the Hi-Power, but we’ll get there.) The 1911 introduced the short recoil operating system with a tilting barrel. Lockup occurs through barrel lugs engaging matching recesses in the slide, with the swinging link facilitating unlocking during recoil.

This is not just historically important; it’s practically important. The vast majority of modern semi-automatic pistols still use some version of this principle. When you hold a 1911, you’re holding the template. A good World War I-era or early military contract model is ideal, because that’s the design in its purest, least modified form.

The High-Capacity Staggered Magazine. Now here’s a shift that doesn’t get enough credit outside collector circles. The Browning Hi-Power began as Browning’s design before his death in 1926. While Browning laid the groundwork, Dieudonné Saive at FN in Belgium finalized the pistol and is credited with perfecting its double-stack magazine system. The result: 13 rounds of 9mm in a grip that was still reasonably sized for a human hand.

Previous pistols gave you seven or eight rounds in a single-stack column. The Hi-Power said, “What if we just stagger them?” That mechanical shift redefined what a military service pistol could be, and its DNA runs through basically every modern duty gun. Finding a pre-war FN-produced Hi-Power is the gold standard, but even post-war military contract examples carry serious collector and mechanical significance.

Polymer Frames and Striker-Fired Actions. And then there’s the Glock 17. I know. Some collectors roll their eyes at the idea of a plastic gun being “collectible.” But you cannot tell the story of mechanical innovation in handguns and leave out Gaston Glock’s 1982 design.

While not the first polymer-framed pistol (the HK VP70 preceded it in 1970), the Glock 17 was the first to achieve widespread military and law enforcement adoption. It proved its durability through rigorous Austrian military trials, and its “Safe Action” system, a partially pre-cocked striker that completes tension during the trigger pull, showed that a mechanism with no external hammer and no traditional single-action or double-action trigger could be trusted by armed professionals worldwide.

Love it or hate it, every modern polymer striker-fired pistol, the Smith and Wesson M&P, the Springfield XD, the SIG P320, is a descendant. First-generation Glock 17s, especially early Austrian military or police issue examples, are the ones to chase.

Once You’ve Got the Foundation, the Real Personality Emerges

The milestones above are the obvious ones, and they should form your collection’s backbone. But some of the most fascinating engineering in handgun history happened off the beaten path, in designs that took a completely different approach to solving familiar problems. This is where a mechanical innovation collection gets really fun.

Bottom-Barrel Revolvers. The Chiappa Rhino is a modern example that makes people do a double-take. Instead of firing from the top chamber of the cylinder, like virtually every revolver since Colt’s day, the Rhino fires from the bottom. Why? Because it reduces rotational muzzle flip by aligning recoil force closer to the shooter’s wrist axis, though total recoil energy remains unchanged.

The Rhino looks strange, almost like a sci-fi prop, but the engineering logic is sound. It represents a willingness to question a fundamental assumption that went unchallenged for over 170 years. That kind of thinking deserves a spot in your collection.

Modular Chassis Systems. This is newer territory, and it’s still evolving. The SIG Sauer P320 and, to a degree, the Beretta APX took the concept of “what is the gun, really?” and gave a radical answer. In the P320’s case, the serialized component, the part that is legally the firearm, is a small stainless steel chassis that holds the fire control group. You can pull that chassis out and drop it into different-sized grip modules, pair it with different slides and barrels, essentially building different guns around the same core.

While modular concepts existed before (the SIG P250 used a similar serialized-frame approach), the P320 was the first to mainstream a removable serialized chassis at scale. The U.S. military’s adoption of it as the M17/M18 validated the concept. As a collector, early P320 models or the military-contract M17 are worth having as markers of this shift.

Gas-Sealed Revolvers. If you want something truly obscure, look at the Russian Nagant M1895. Its cylinder moves forward upon cocking to seal the gap between the cylinder and the barrel. Most revolvers lose a bit of gas pressure at that gap; the Nagant eliminates it. This also made it one of the only revolvers that could be suppressed. Though suppression was modest compared to semi-autos, it was uniquely effective for a revolver platform.

It’s a strange solution to a problem most designers just accepted, and it gives your collection a real conversation piece. These oddball designs aren’t just curiosities. Each one represents an engineer asking, “What if we did it differently?” That’s the spirit of an innovation-focused collection.

Condition Matters More Than You Think

When you’re collecting for mechanical significance, the internals matter far more than the finish. A Luger P08 with a gorgeous blued exterior but a mismatched toggle assembly and replaced sear spring is basically a pretty shell. It doesn’t tell the mechanical story you’re trying to preserve.

You want original parts. Matching serial numbers across all major components. Evidence that the action still functions the way its designer intended.

A little honest wear on the outside is fine; it means the gun was used, which is what it was made for. But a “Frankengun” cobbled together from parts bins loses its value as a pure example of a specific era’s engineering. It becomes an approximation instead of an artifact.

This is especially critical with older pieces like the Colt 1860 or early Lugers. These guns are well over a century old, and parts replacement was common over their service lives. Take the time to verify provenance. Get a qualified appraiser involved if you’re spending serious money. The premium for an all-matching, mechanically complete example is steep, but it’s where the real historical and collector value lives.

The C&R License: Your Best Practical Tool

If you’re collecting guns that are at least 50 years old, and a mechanical innovation collection will naturally include many of them, you should seriously consider getting a Type 03 Curio and Relic (C&R) license from the ATF. The application process is straightforward, the fee is modest, and the benefits are significant.

With a C&R license, firearms that qualify as curios or relics (generally those manufactured more than 50 years ago, or guns listed on the ATF’s specific C&R list for being “novel, rare, or bizarre”) can be shipped directly to your home from other C&R holders or dealers. No need to go through a local FFL for every transaction. It simplifies the logistics of building a collection considerably, especially when you’re buying from out-of-state sellers or at online auctions.

The ATF’s definition of “novel, rare, or bizarre” is actually pretty broad, and many mechanically significant firearms qualify simply by age. Your 1911, your P08, your Hi-Power, your Colt 1860? All eligible. It’s a practical tool for a collector, and it signals to sellers that you’re serious, which can open doors.

Document the Why, Not Just the What

This is the part that separates a thoughtful collection from a random accumulation. For every piece you acquire, write down why it’s there. Not just “Colt 1911, .45 ACP, serial number such-and-such.” That’s inventory. What you want is context.

Why does this gun matter mechanically? What problem did its design solve? What came before it, and what came after? How does it connect to the next piece in your collection?

When you can walk someone through your display and explain the transition from revolving cylinders to toggle-lock actions to short recoil systems to polymer frames, you’re not just showing off guns. You’re narrating two hundred years of mechanical problem-solving. That narrative is what gives the collection its coherence and its weight.

Keep a physical notebook or a detailed digital file for each piece. Include photographs of the internal mechanisms, notes on the engineering principles, references to relevant patents, and any provenance documentation. This record becomes part of the collection’s value over time, both intellectually and financially.

Budgeting and Patience: The Unglamorous Realities

Building this kind of collection takes time and money. A good Colt 1860 can run anywhere from a few thousand dollars for a worn but complete example to well into five figures for a pristine specimen with documented history. Luger P08s vary wildly depending on manufacturer, date, and matching status. Even Glock 17 Gen 1 pistols are starting to command premiums as people realize their historical significance.

The temptation is to rush, to snap up the first example you find of each milestone gun because you’re excited about filling in the timeline. Resist that. A mediocre example bought in haste is worse than a gap in your collection.

The right piece at the right price will come along. Talk to other collectors. Haunt gun shows, both local and major collector events such as the Las Vegas Antique Arms Show, the Baltimore show, or regional historical arms exhibitions. Build relationships with reputable dealers who specialize in collectible firearms. They’ll know when something special surfaces, and they’ll think of you.

Set a budget per year if that helps you pace yourself, and be willing to save up for a significant acquisition rather than spreading your money thin across lesser examples.

Think About the Gaps You Can’t Fill Yet

One of the more satisfying aspects of this kind of collection is that it’s never truly finished. Mechanical innovation in handguns didn’t stop with the Glock. New ideas keep emerging.

Look at the Laugo Arms Alien, a competition pistol from the Czech Republic that uses a fixed barrel and a gas-delayed blowback system rather than traditional locked breech or recoil operation, keeping the bore axis extraordinarily low. Or consider the Hudson H9, which, despite the company’s unfortunate closure, attempted to combine 1911 ergonomics with a striker-fired system and a remarkably low bore axis using a unique recoil spring arrangement. Some of these newer designs will prove to be historical footnotes; others might turn out to be the next tipping point.

Keeping an eye on emerging engineering, and maybe picking up early examples before everyone else catches on, is part of the collector’s game. Technologies like biometric safeties and electronic firing systems are still developing, and early production models could gain significance if those concepts take hold.

Displaying and Sharing the Story

A collection like this deserves more than a dark safe. Obviously, security comes first, and you should store your firearms according to all applicable laws and with appropriate safes, locks, and insurance.

But think about how you present the collection when you do show it. Arrange pieces chronologically or by mechanical principle. Use labels that explain the engineering, not just the model name. If you’ve got the space, a wall-mounted timeline display with brief placards for each piece can be incredibly compelling.

Some collectors photograph their pieces alongside exploded diagrams or patent drawings, creating visual pairings that emphasize the mechanical story. And share it. Talk to other collectors, join forums, write about your pieces, participate in historical arms collecting groups like those affiliated with the CRPA or similar organizations. The conversations it generates, the debates about which innovations mattered most, the younger enthusiasts who see the engineering connections for the first time: that’s the payoff.

Bringing It All Together

Building a handgun collection around mechanical innovation is a different kind of challenge than accumulating the most valuable or the rarest pieces (though there’s plenty of overlap). It requires you to understand how things work, not just what they’re worth. It asks you to see each firearm as a chapter in a longer story of human ingenuity, where each designer inherited the previous generation’s best ideas and tried to push past their limitations.

Start with the undeniable milestones: the revolving cylinder, the toggle-lock, the short recoil tilting barrel, the double-stack magazine, the polymer striker-fired pistol. Build outward from there into the unconventional and the experimental. Prioritize mechanical completeness and originality over cosmetic perfection. Get your C&R license. Document everything. Be patient.

And when someone asks you about your collection, don’t just tell them what you own. Tell them why each piece changed what came next. That’s the collection talking, and honestly, it’s the best part.

Frequently Asked Questions

Start by identifying the engineering “tipping points” that changed firearm design, like the revolving cylinder, toggle-lock, short recoil system, double-stack magazine, and polymer striker-fired action. These milestones form the backbone of your collection before you branch into more unconventional designs.

The Colt Paterson/1860 Army, Luger P08, Colt 1911, Browning Hi-Power, and Glock 17 each introduced a mechanism that fundamentally shifted the design of handguns. Together, they trace roughly two hundred years of engineering evolution.

Internal condition wins, hands down. A mechanically complete example with matching original parts preserves the engineering story you’re collecting, while a refinished “Frankengun” with swapped internals is just an approximation.

A Type 03 Curio and Relic license from the ATF lets you have qualifying firearms (generally 50+ years old) shipped directly to your home without going through a local FFL. It’s not required, but it simplifies logistics and signals to sellers that you’re a serious collector.

Absolutely. Designs like the Chiappa Rhino’s bottom-barrel firing, the SIG P320’s modular chassis system, and the Laugo Alien’s gas-delayed blowback represent engineers questioning long-held assumptions, and early examples could become tomorrow’s milestones.