Key Takeaways:

- Investment-Grade Is a Discipline, Not a Dollar Amount: An investment-grade gun collection isn’t defined by how much money you’ve spent, it’s defined by how deliberately you manage what you own. Documentation, originality, historical context, and market awareness matter more than price tags. A well-documented, historically important $10,000 firearm can outperform a poorly documented $50,000 showpiece every time. Value comes from structure and intent, not just acquisition.

- Liquidity, Documentation, and Preservation Are What Turn Firearms into Assets: A firearm only becomes a true asset when it can be verified, preserved, insured, and sold efficiently. Provenance files, condition records, climate-controlled storage, proper insurance, and clear exit strategies aren’t optional extras, they are the mechanisms that protect value and enable intelligent liquidation. Without these systems in place, even exceptional firearms remain personal possessions rather than strategic holdings.

- The Real Divide Is Mindset, Passion Versus Portfolio Thinking: Hobby collectors buy what they love and keep it indefinitely. Investment-grade collectors love firearms too, but they evaluate them with emotional discipline. They specialize, track markets, plan exits, and accept that some pieces are held temporarily rather than forever. The moment a collector can separate appreciation from attachment is the moment a collection begins to function as a portfolio instead of a passion project.

There’s a moment that every firearms collector experiences. You’re standing in your safe, looking at the dozen or so pieces you’ve accumulated over the years, and you start wondering: am I building something of real value here, or just indulging a passion?

It’s not always an easy question to answer. The line between a serious investment-grade collection and a hobby collection can seem blurry at first glance. Both might contain beautiful firearms. Both might represent thousands of dollars and countless hours of research. But the difference, when you really examine it, runs deeper than most people realize.

Let me be clear from the start: there’s absolutely nothing wrong with being a hobby collector. Some of my favorite people in this community are passionate enthusiasts who buy what they love, shoot what they enjoy, and couldn’t care less about appreciation rates or market trends. That’s a perfectly valid approach to the hobby. But if you’re reading this, chances are you’re curious about the other path, the one where your collection becomes a legitimate asset class, something that grows in value and could be liquidated strategically when needed.

This article is written for collectors who view firearms as long-term assets, not just personal possessions. If you’re at that threshold where your collection’s value warrants more sophisticated management, or you’re deliberately building toward that goal, these distinctions matter.

So what actually separates these two approaches? Let’s talk about it.

Price Doesn’t Equal Investment Potential

Here’s something that trips up a lot of collectors: expensive and investment-grade aren’t the same thing.

I’ve seen $50,000 firearms that are terrible investments. Beautiful pieces, indeed. Museum-quality craftsmanship, absolutely. But poor documentation, over-restoration, or niche appeal that limits buyer pools can turn an expensive gun into an illiquid asset that barely holds its value.

Conversely, I know collectors sitting on $8,000 to $12,000 pieces that appreciate steadily year after year because they occupy specific historical niches with growing scholarly interest and strong documentation. One guy I know picked up a well-documented WWI contract Colt for under $10,000 seven years ago. Today? He’s turned down offers of $18,000 because the trajectory suggests he should wait a few more years.

Investment-grade isn’t about the price tag. It’s about documentation, condition standards, historical significance, market knowledge, and strategic positioning. You can spend six figures building a hobby collection, or you can spend $30,000 building the foundation of a genuinely appreciating asset portfolio. The difference is in approach, not dollars.

Documentation Isn’t Optional; It’s Everything

Here’s the thing about investment-grade firearms: provenance matters as much as the gun itself, maybe more.

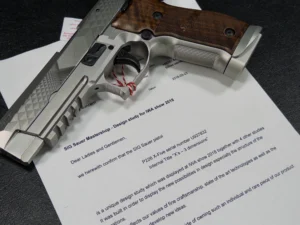

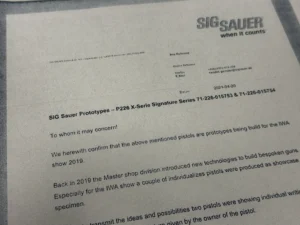

A hobby collector might keep a receipt in a drawer somewhere. An investment collector maintains a comprehensive archive that would make a museum curator jealous. We’re talking original purchase receipts, letters of authenticity, historical documentation, previous ownership records, professional appraisals, condition reports over time, and photographs documenting every detail of the firearm at the time of acquisition.

Why does this matter so much? Because in the high-end firearms market, the story behind a gun can double or triple its value. A Colt Single Action Army revolver is one thing. That same Colt with documented provenance linking it to a specific historical figure or event? That’s something entirely different.

Documentation is part of the asset, not just paperwork about the asset. I watched an estate sale a few years back where two nearly identical Springfield Model 1903 rifles sold. One had complete military documentation, issue records, unit assignments, and even photographs of the soldier to whom it was issued. It brought $8,200. The other, virtually identical in condition but with no documentation? $2,800. Same gun, different stories, drastically different values.

Investment-grade collectors understand that documentation isn’t busywork; it’s the foundation of value. They maintain records of any restoration work, replacement parts, or conservation efforts. They keep condition reports at regular intervals, often photographed and dated by professionals who follow museum or archival standards. They know which expert evaluated their piece and when. They keep correspondence with auction houses, dealers, and other collectors.

Think of it this way: if you had to sell your entire collection to a serious buyer tomorrow, could you hand them a folder (or digital file) for each piece that tells its complete story? If the answer is no, you’re probably running a hobby collection.

Condition Standards That Actually Mean Something

Hobby collectors often use terms like “excellent condition” or “nice shape” pretty loosely. And honestly? That’s fine for personal enjoyment. But investment-grade collecting requires an entirely different level of precision.

The NRA firearms condition standards, widely recognized as industry benchmarks, are in place for a reason. Factory New, Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, Poor, these aren’t casual descriptions. They’re specific grades with defined criteria that directly impact market value. A gun in NRA Excellent condition might be worth three times what the same model in Good condition commands.

Investment collectors don’t just understand these standards; they’re borderline obsessive about them. They know that “finish wear on high edges” has a different implication than “scattered pitting.” They recognize that a replaced spring affects the value differently than a replaced barrel. They understand terms like “reblued” or “refinished” are often warning signs that can significantly impact investment potential.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Originality beats cosmetics. A truly sophisticated investor also understands when the conditions and standards shift for specific categories. A well-used Civil War cavalry carbine with honest wear might be more desirable and more valuable than an arsenal-refinished example that looks prettier but lost its originality. Original patina and wear patterns tell a story.

Proper restoration, when necessary and properly documented, doesn’t always destroy value. But improper or undocumented restoration? That’s a different story. A collector once showed me a Colt Dragoon that had been “restored” by a well-meaning gunsmith who reblued it and refinished the grips. In its original condition, that gun should have been worth $15,000 to $18,000. Post-restoration? It struggled to fetch $7,500 at auction because the originality was gone.

Hobby collectors sometimes make the mistake of “improving” a firearm by cleaning, polishing, or refinishing it. They’re trying to make it nicer. Investment collectors understand that careful, documented conservation preserves value while over-enthusiastic improvement destroys it.

Historical Significance Changes the Game Completely

You can collect Winchester lever actions because you think they’re cool (valid). Or you can collect Winchester lever actions because you understand their role in westward expansion, the evolution of repeating firearms technology, and their cultural impact on American identity (investment mindset).

See the difference?

Investment-grade collectors don’t just accumulate firearms; they study them. They understand historical context, manufacturing variations, contract specifications, and cultural significance. They know which models were used in which conflicts, which variants are rare because of production numbers, and which features mark a particular year or run.

This knowledge base isn’t just intellectual curiosity. It directly informs purchasing decisions and drives value. A Model 1911 pistol is historically significant. A Model 1911 with documented WWI military-issue markings is more important. A Model 1911 actually carried in combat with verifiable provenance? That’s the kind of piece that appreciates steadily year after year.

Historical significance isn’t universal; it’s category-specific. A rare shotgun variant might matter deeply to scattergun specialists but mean nothing to military collectors. Understanding your niche and its scholarship is crucial.

Historical significance also means understanding market cycles. Specific categories heat up based on anniversaries, exhibitions, or renewed historical interest. The 75th anniversary of D-Day created increased demand for WWII-era firearms. The 150th anniversary of the Civil War did the same for 1860s weaponry. Investment collectors track these trends and position their collections accordingly.

Hobby collectors buy what catches their eye. Investment collectors buy pieces that occupy specific historical niches—preferably undervalued ones that will appreciate as scholarship or public interest grows.

Market Knowledge That Goes Beyond Price Tags

Ask a hobby collector what their guns are worth, and you’ll probably get ballpark figures based on what they paid. Ask an investment collector the same question, and you’ll get a detailed breakdown of current market conditions, recent auction results, trends over the past five years, and projections for future appreciation.

Investment-grade collecting requires treating firearms like any other asset class. That means tracking values, understanding market cycles, and recognizing when categories are overheated or undervalued. It means knowing the difference between retail prices, auction results, and private sale values. It means understanding that specific dealers cater to collectors while others serve shooters, and pricing varies dramatically between these markets.

Serious investors subscribe to auction catalogs from auction houses such as Rock Island Auction Company, Morphy Auctions, and Heritage Auctions. They track results religiously, not just final prices, but bid patterns, regional variations, and seasonal trends. They follow specialized dealers and know which ones command premium prices due to their reputations for authenticity and quality. They understand regional variations—a Sharps rifle might command different prices, particularly in private sales, even as online auctions have narrowed regional gaps somewhat.

Liquidity is not the same as value. Some firearms are incredibly valuable but difficult to sell because the buyer pool is small. Others might be less valuable but move quickly because demand is broad. An investment collector balances their portfolio between blue-chip assets that retain value and more liquid assets that can be converted to cash if needed.

Market timing matters too. Buying at a gun show, where emotions run high, versus negotiating a private sale months after an estate enters the market, these situations present different opportunities. Investment collectors develop patience and discipline. They don’t chase every interesting piece. They wait for the right firearm at the right price with the proper documentation.

Storage and Preservation Are Non-Negotiable

Hobby collectors might keep firearms in a standard safe, maybe with some desiccant packets thrown in. That works fine if you’re mainly worried about theft and meeting insurance requirements.

Investment collectors? They’re running essentially climate-controlled archival storage.

Temperature and humidity control aren’t optional when you’re preserving assets worth tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars. Rust, pitting, wood degradation, and finish deterioration are problems that develop slowly and can destroy value before you notice. Investment-grade storage means maintaining stable conditions year-round, monitoring humidity levels religiously, and using proper conservation techniques borrowed from museum practices.

This also extends to handling. Investment collectors use controlled handling methods, proper support techniques, clean hands or appropriate gloves when necessary, and careful attention to how pieces are moved and stored. They understand that careless handling accelerates wear. They know how to support a firearm when moving it properly. They never lean guns against each other where finishes can rub. They store pieces individually, often in custom cases or racks that prevent damage from contact.

Conservation versus restoration is another critical distinction. Hobby collectors might take a rusty gun to a smith and ask them to “fix it up.” Investment collectors consult with conservation specialists who understand period-correct techniques and materials. They know when intervention is necessary to prevent further deterioration and when it’s better to stabilize and leave alone.

Some investment collectors even maintain detailed environmental logs for their storage areas. Sounds extreme? Maybe. But when a single Paterson Colt can sell for half a million dollars, extreme starts looking like prudent asset management.

Insurance and Security Reflect the Stakes

Your homeowner’s policy probably covers firearms up to a specific limit, typically around $2,500. That’s adequate for a modest hobby collection. It’s laughably insufficient for an investment-grade collection where individual pieces might exceed that limit.

Investment collectors maintain specialized firearms insurance through companies that understand collectible weapons. These policies schedule items individually with agreed-upon values based on professional appraisals. They cover not just theft but also damage, loss, and, in the event of a total loss, even changes in market value.

Proper insurance validates your collection’s value. It forces regular appraisals, documentation updates, and realistic market valuations. The process of ensuring adequate documentation often reveals weaknesses in documentation or gaps in condition records.

Security follows the same pattern. A hobby collector might have a good safe bolted to the floor. An investment collector has a vault-quality safe (or multiple safes), alarm systems with specific zones for the gun room, cameras, motion sensors, and redundant security measures. Some even maintain off-site storage for their most valuable pieces or rotate inventory between locations.

This isn’t paranoia. It’s risk management. When you’re sitting on six or seven figures worth of collectible firearms, adequate security isn’t optional; it’s basic portfolio management.

Exit Strategy and Liquidity Planning

Here’s something hobby collectors rarely think about: how will this collection be liquidated?

Investment collectors think about this constantly. They understand that a collection is only an asset if it can be converted to cash when needed. Liquidity planning often matters more than appreciation. A gun that’s appreciated 30% but takes two years to sell at full value isn’t as useful as a piece that’s appreciated 20% but moves in thirty days.

This means maintaining relationships with dealers and auction houses. It means understanding consignment agreements, buyer’s premiums, and seller’s commissions. It means having appraisals current enough to support estate planning or divorce proceedings (yes, firearms collections come up in both contexts regularly).

Time-to-cash matters. Sophisticated investors diversify liquidity within their collections. Maybe 30% in pieces that could sell within a week through established dealers. Another 40% in mid-range items that might take a month or two to move at fair prices. The final 30% in premium pieces that require patient marketing but represent the core investment value.

Market access matters. Some firearms do better at specialized auctions where knowledgeable collectors compete for rare items. Others might move faster through private sales to established collectors. Understanding which pieces fit which markets—and maintaining connections to those markets—makes the difference between an orderly liquidation and a fire sale.

I know of an estate where the executor, himself a knowledgeable collector, took 18 months to liquidate a $400,000 collection methodically. By choosing the right venues for each piece and carefully timing sales, he realized $485,000. Another estate, rushed through a single auction house without proper preparation, netted barely $220,000 on a comparably valued collection. The difference? Strategic liquidity planning.

Knowledgeable executors matter. Investment collectors have detailed inventories, appraisals, and instructions for their heirs. They’ve discussed their collection with estate attorneys and made provisions for executors who won’t dump everything at the local gun shop for pennies on the dollar.

The Emotional Difference That Really Matters

Here’s the most brutal truth about investment-grade collecting: you can’t fall in love with every piece.

Hobby collectors buy guns they’re passionate about. They fondle their favorites, take them to the range, and show them off to friends. The collection is deeply personal. Each piece has a story about why they bought it, what they felt when they first held it, and memories attached to it.

Investment collectors need emotional distance. Not complete detachment, passion for firearms is what drives this hobby in the first place. But they need the ability to evaluate pieces objectively, recognize when something should be sold, and pull the trigger (so to speak) on liquidating a gun even if they personally love it.

This doesn’t mean investment collectors don’t appreciate their firearms. Many are passionate students of history and craftsmanship. But they maintain perspective. A gun that’s appreciated 40% over five years but has plateaued might need to be sold to fund a better opportunity, even if it’s a beautiful piece they enjoy owning.

Hobby collectors keep guns forever. Investment collectors hold them as long as they make strategic sense. That’s a fundamental mindset difference.

Specialization Versus Variety

Walk into a hobby collector’s safe, and you might see a little bit of everything. A couple of revolvers, a few military rifles, maybe a shotgun or two, that one weird gun they found at an estate sale. It’s eclectic, personal, and reflects their broad interests.

Investment-grade collections tend toward specialization. Maybe it’s Colts from a specific era. Perhaps Winchester lever actions with a focus on rare variants. Or U.S. martial pistols with complete documentation. This focus serves multiple purposes.

Deep expertise drives better decisions. You can’t be an expert on everything, but you can become the go-to person on Remington Rolling Block rifles or Smith & Wesson top-break revolvers. This expertise informs better purchasing decisions and often provides access to pieces that never hit the open market because dealers call specialists first.

Second, specialized collections often command premiums when sold as complete collections. A comprehensive, well-documented collection of Springfield trapdoor rifles with all major variants represented is worth more than the sum of its parts. Serious collectors or institutions might compete to acquire the entire collection intact.

Third, specialization creates market identity. When you’re known as “the guy” for a particular category, people bring you first refusal on pieces. You get tips about estate sales before the public does. Dealers call you when something special comes through. This network effect compounds over time.

Hobby collectors follow their curiosity wherever it leads. Investment collectors channel their passion into specific niches where expertise translates to returns.

The Portfolio Approach to Building Value

Investment collectors don’t just buy firearms; they build portfolios. This means thinking about balance, diversification, and strategic positioning.

A well-structured investment collection might include anchor pieces (expensive, historically significant firearms that serve as the core), growth potential items (undervalued pieces from emerging categories), cash flow pieces (moderately priced guns with steady demand that can be sold quickly if needed), and speculative additions (calculated risks on pieces that might appreciate dramatically if specific trends develop).

This diversification protects against market volatility. If the military collector market softens but Western artifacts heat up, a balanced portfolio maintains overall value. It’s the same principle that drives any investment strategy: don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

Hobby collectors buy what they like. Investment collectors like what they buy, but they also consider how each piece fits into their broader strategy. Sometimes that means passing on a gun they’d personally love to own because it doesn’t align with portfolio goals.

A Quick Self-Assessment

If you’re wondering where your collection falls on this spectrum, ask yourself these questions:

Do you have documented provenance for each piece? Not just a receipt, but historical documentation, authenticity letters, and previous ownership records, where applicable.

Could you liquidate 25% of your collection within 30 days at fair market value? Do you have the dealer relationships and market knowledge to execute this?

Are your firearms insured under a scheduled collectibles policy? Does each piece have an agreed-upon value with your insurer?

Do you track auction results in your collecting category? Can you cite recent comparable sales and market trends?

Have you made provisions for knowledgeable liquidation in your estate planning? Would your heirs know how to realize fair value?

Is your storage environment monitored and controlled? Are you actively preventing deterioration, not just hoping for the best?

If you answered “no” to more than two of these, your collection is likely a hobby collection, and again, there’s nothing wrong with that. But if you’re trying to build investment-grade holdings, these gaps need to be addressed.

Bringing It All Together

So what really distinguishes an investment-grade collection from a hobby collection? It’s not just money, though investment collections generally involve larger capital outlays. It’s not just quality, though investment pieces typically represent higher standards.

The real difference is mindset. Investment collectors view firearms as assets that are historically significant and aesthetically pleasing. They maintain rigorous documentation, understand market dynamics, prioritize preservation, liquidity plan, and balance passion with strategic discipline.

Hobby collectors approach firearms as passions that happen to have some monetary value. They buy what moves them, keep what they love, and enjoy the community and history without the pressure of portfolio management.

Neither approach is better than the other. They’re just different paths through the same fascinating world. Some collectors start as hobbyists and gradually transition toward investment-grade practices as their collections grow in value and sophistication. Others remain passionate hobbyists their entire lives and wouldn’t want it any other way.

If You’re Making the Transition

If you’re at that inflection point—where your collection’s value has crossed into territory that warrants more sophisticated management, or you’re deliberately building toward investment-grade holdings, the path forward requires commitment.

Start with documentation. Retroactively building provenance files for existing pieces might feel tedious, but it’s foundational work that pays dividends. Get professional appraisals from recognized experts in your categories. Photograph everything comprehensively.

Develop your market knowledge systematically. Subscribe to auction catalogs. Track results. Build relationships with reputable dealers. Join specialized collector organizations where serious investors share insights.

Reassess your storage and insurance. Climate control isn’t glamorous, but it preserves value. Proper insurance forces discipline about documentation and realistic valuations.

Think about your exit strategy now, not later. Who would buy your collection? How would they find out about it? What would make it more attractive to serious buyers?

And be honest with yourself about emotional attachment. If you can’t imagine selling certain pieces regardless of market opportunity, maybe keep them, but recognize they’re personal holdings, not investment positions. Build your investment strategy around pieces where you can maintain objectivity.

The collectors who understand these distinctions, who embrace the responsibilities along with the rewards, are the ones building collections that stand the test of time, not just as personal treasures, but as genuine assets that preserve history while building wealth.

In the next step, the question becomes not what to collect, but how to structure a collection once it crosses into asset territory.

Frequently Asked Questions

Investment-grade firearms are defined by verifiable originality, documentation, historical relevance, market demand, and liquidity, not by price alone. A firearm becomes investment-grade when its value can be defended to a knowledgeable third party, an auction house, insurer, estate attorney, or serious buyer, using evidence rather than opinion.

No. High price does not equal investment quality. Firearms with poor documentation, over-restoration, or narrow buyer appeal can be expensive yet illiquid and stagnant in value. Conversely, modestly priced firearms with strong provenance, originality, and relevance to a well-studied niche often appreciate more reliably over time.

Not all, but many do. Certain categories, military-issued arms, early production variants, limited contract guns, or historically associated pieces, depend heavily on provenance. Other categories rely more on intrinsic rarity, originality, and condition. What matters is whether the firearm’s value can be justified clearly within its collecting niche.

No, but undocumented or inappropriate restoration often does. Proper, period-correct conservation performed by qualified specialists and fully documented can preserve or even protect value. Cosmetic restoration intended to make a firearm “look new” usually removes originality and reduces investment potential.

Because the market values certainty. Without documentation, buyers must rely on trust or assumptions, which limits demand and suppresses prices. Documentation transforms a firearm from an object into a verified historical artifact, making it easier to insure, appraise, and sell at full market value.