Key Takeaways:

- Placement and method can make or break value. Not all import markings hit collectors’ wallets equally hard. A billboard stamp on a visible surface can shave 10–20% off a firearm’s market value, while a discreet mark tucked inside a magazine well barely registers. How an importer handles the requirement says a lot, and serious collectors have long memories about who does it well.

- No import mark tells a story, but verify before you believe it. The absence of commercial import markings keeps the door open to restoring provenance, and that carries real, price-affecting weight in the collector market. Here’s the thing, though, “no mark” doesn’t automatically mean “battlefield trophy.” It might just mean the gun arrived before 1968. Documentation is what separates a compelling story from a convenient one.

- Import markings are authenticity filters, whether you like them or not. Honestly, this is the part collectors sometimes overlook. A Century Arms stamp on a gun someone claims was “personally captured from an officer” doesn’t just lower the price; it collapses the story entirely. That’s not a bad thing. For buyers willing to read the markings carefully, they’re one of the most reliable reality checks available in a market where romantic provenance can inflate prices well beyond what the hardware actually justifies.

There’s a moment every serious collector knows. You’re at a gun show, or maybe scrolling through an auction listing at midnight, and you spot it, a gorgeous Luger P08, blued steel catching the light, matching serials, the kind of piece that makes your pulse tick a little faster. Then you flip it over. There it is. “CENTURY ARMS, ST. ALBANS VT” stamped right on the barrel in letters big enough to read from across a room.

The excitement doesn’t disappear entirely, but it changes. That stamp changes things. And understanding why it changes things, legally, historically, and financially, is something every collector should have a firm grasp of.

Let’s get into it.

The Stamp You Didn’t Ask For (But the Law Requires)

First, a bit of context. The United States has some of the most detailed firearm marking requirements in the world, and for imported guns, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives lays it out pretty clearly. Any firearm brought into the country for commercial sale must bear the importer’s name, city, state, and the country of origin. No exceptions, no workarounds.

Since 2002, the regulations tightened further. Markings must be at least 0.003 inches deep and no smaller than 1/16 inch in print size, specifically so they can’t be easily ground off or obscured. The reasoning is straightforward: traceability. Federal Firearms License holders need to log these guns in their “bound books,” and law enforcement needs a reliable paper trail if a firearm ever turns up at a crime scene. That’s not a controversial goal. Most people, collectors included, understand why that system exists.

But understanding something doesn’t mean you have to like it.

The problem isn’t the requirement itself. It’s the execution. Because when you’re talking about a World War II-era German pistol with original proof marks, a factory finish that’s somehow survived 80 years, and matching numbers throughout, slapping a modern importer’s address on the barrel feels a little like spray-painting your name on a Rembrandt. Legally necessary in certain contexts, aesthetically devastating.

“Billboard” Markings and the 10–20% Hit

Here’s where it gets financially concrete. The collector community has a name for oversized, conspicuous import stamps: billboards. It’s not a compliment.

A billboard marking, think large block lettering stamped prominently on the barrel, frame, or receiver, can reduce the market value of a high-end collectible by anywhere from 10% to 20%, depending on the gun and how visible the marking is. On a firearm that might otherwise sell for $2,000, that’s $200 to $400 gone, just like that. On rarer pieces with higher price tags, the loss scales accordingly.

The math gets worse when you factor in collector psychology, which is honestly just as important as any objective measure of condition. Collectors aren’t just buying metal and wood. They’re buying a piece of history, a tactile connection to another era. When a modern importer’s address intrudes on that, it breaks the spell. Even collectors who fully understand the legal necessity of the marking often describe a visceral reaction to seeing it, a slight disappointment that no amount of rationalizing quite erases.

Some importers have taken this seriously. Simpson Ltd, which has built a reputation among serious collectors, uses specialized equipment to place markings in genuinely discreet locations: under the barrel, inside the magazine well, places that don’t interrupt the firearm’s visual flow. The marking is there, it has to be, but you have to look for it. That approach preserves far more of the gun’s presentation value, and collectors notice. Guns imported by houses that care about placement routinely command better prices than identical models marked by importers who treated the requirement as a formality.

It’s a small thing with a real-world impact.

The “Bring-Back” Question Romance, Reality, and a Little Bit of Both

Now here’s where the absence of import marks gets interesting.

When you encounter a foreign military firearm with no import markings at all, a few explanations are possible. The most historically significant: it came home with a veteran. Bring-backs, firearms personally carried or shipped home by American servicemen after World War II, Korea, or Vietnam, didn’t require commercial import markings because they weren’t entering commerce. They were personal property.

The Gun Control Act of 1968 significantly changed the landscape. Before that, the import marking requirements we know today simply didn’t exist in their current form. So a gun that arrived in the U.S. before 1968 might have no markings because it’s a bring-back, but because it predates the requirement entirely.

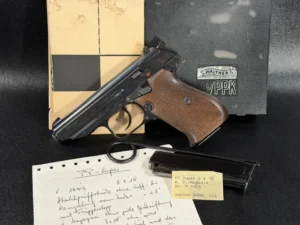

Still, the bring-back story carries weight in the collector world, real, tangible, market-affecting weight. A Walther P38 with a credible bring-back provenance, matching paperwork, maybe a photo of a serviceman holding it in Germany, can sell for a notable premium over an otherwise identical gun imported commercially. The story isn’t just sentimentality. It’s a documentation of a unique, unbroken chain of custody that connects the firearm directly to a specific historical moment.

The absence of import marks preserves the possibility of that story, even when the story can’t be confirmed. That ambiguity has value.

When the Story Doesn’t Hold Up

Here’s the flip side, and it matters.

Every so often, you’ll encounter a seller, at a show, in an online listing, sometimes with complete conviction, who tells you a firearm was “captured from a high-ranking officer” or “taken off the battlefield” and has been in the family ever since. Dramatic. Appealing. Potentially worth believing.

Then you look at the barrel and see “CENTURY ARMS, ST. ALBANS VT.”

Century Arms is one of the largest importers of surplus military firearms in the United States. They’ve been operating since the 1960s. A Century Arms import mark is not subtle; it’s not the kind of thing that gets added retroactively. If that stamp is there, the gun came through commercial import channels, period. The battlefield capture story is, at that point, a fabrication, whether the seller knows it or not.

This is one of the genuinely useful functions of import markings that doesn’t get enough credit. They’re authenticity filters. A knowledgeable buyer who knows which importers were active when, and what their markings look like, can immediately reality-check a seller’s provenance claims. It doesn’t make you cynical; it makes you informed. And in a market where romantic stories can inflate prices well beyond what the hardware justifies, that information is worth having.

The Technical Side of Getting It Right

Not all import markings are created equal, and the method matters as much as the placement.

Traditional firearms manufacturers used roll marking, a process where a hardened steel die is rolled under pressure across the metal surface, displacing material cleanly and leaving a crisp, deeply recessed impression. The result is visually similar to the markings that came on the gun originally, which is one reason original manufacturer stamps tend to look “right” even on century-old guns.

Modern importers, facing cost and equipment constraints, often turn to laser etching or dot-matrix pinning instead. Laser etching burns material away rather than displacing it, and while the technology has improved considerably, the results still have a different character than roll marking. Dot-matrix pinning uses a series of closely spaced punch points to form letters and numbers. Both methods are perfectly legal and meet ATF depth and size requirements, but to a collector’s eye, and particularly under a loupe or raking light, they look different. Less integrated. More like something added later, because they are.

The ATF does specify that markings must not cause “unsafe deformation” of the barrel or receiver. That’s a structural integrity requirement, not an aesthetic one. But it does mean importers can’t just stamp wherever they want as aggressively as they want. There are limits, and responsible importers work carefully within them.

Does It Matter for Every Gun Equally?

Short answer: No, and the variation is pretty significant.

For common military surplus firearms, think Mosin-Nagants, various SKS variants, the ubiquitous surplus pistols that arrived by the shipload in the 1980s and 90s, import markings barely register as a concern. These guns were never going to be fine-collection pieces for most buyers. They’re shooters, range guns, affordable history. A Century Arms stamp on a $300 rifle matters about as much as a price sticker on a used paperback.

The calculus changes completely for higher-tier collectibles. Pre-war commercial Lugers. Mauser Broomhandles in matching configuration. Colt Single Action Army revolvers with original finish. High-condition Walther PP pistols from the right era. For these guns, condition and originality are everything. Every imperfection compounds, and an import marking is, by definition, a modification from the original state. It’s not damage in the traditional sense, but it’s not original either.

For the very top tier, genuinely rare variants, documented bring-backs with full provenance, exhibition-quality pieces that belong in serious collections, import marks essentially don’t appear, because guns at that level simply don’t enter the commercial import stream. They move through estate sales, specialized auction houses like Rock Island Auction, and private collector networks.

How CZ Forum Discussions Reveal Collector Priorities

It’s worth paying attention to the conversations collectors actually have. Forums like the Original CZ Forum, r/milsurp on Reddit, and similar spaces are where the real-world consensus forms, where collectors with actual buying and selling experience report what they’ve seen affect prices.

The consistent message is nuanced. Collectors don’t universally reject marked guns; that would eliminate too much of what’s available and affordable. What they actually reject is bad markings, visible, conspicuous, sloppily placed stamps that dominate the visual presentation of the firearm. Discreet markings in out-of-the-way locations are accepted, sometimes barely factoring into a price negotiation at all.

There’s also a generational element here. Younger collectors, who entered the hobby after the current import marking regulations were firmly established, tend to have a different relationship with marks than collectors who remember acquiring unmarked imports in the 1980s. For someone who has never seen the market any other way, a discreet importer stamp is just part of the landscape. For a collector who bought Lugers before billboard markings became common, the same stamp is a visible degradation from a standard they personally experienced.

Neither perspective is wrong. They’re just different relationships with the same reality.

The Collector’s Practical Checklist

So what does all of this mean when you’re actually standing in front of a gun, or reading a listing description, trying to make a decision? A few things worth keeping in mind:

Location matters more than presence. A marking inside the magazine well or under the barrel has minimal impact on value and presentation. A marking on the barrel flat or the frame’s visible face is another story entirely.

Know your importers. The major players, Century Arms, CAI, Interarms, Navy Arms, Simpson Ltd, Edelweiss Arms, each have a reputation in the collector community. Researching which importer handled a specific gun can tell you a lot about what to expect in terms of marking quality and placement.

Original proof marks aren’t import marks. Foreign proof marks, manufacturer stamps, acceptance marks, and unit property stamps all add to provenance and value. Don’t confuse them with commercial import marks. They’re a completely different category.

Condition grading should account for markings. When comparing two guns, factor in the billboard marking into the price accordingly. Don’t pay the NRA for excellent prices for a gun whose presentation has been meaningfully compromised.

Ask about documentation. For guns presented as bring-backs or pre-1968 imports, documentation matters. Letters, discharge papers, photos, previous owner correspondence, anything that supports the provenance claim and explains why no commercial import mark appears.

The Deeper Question Underneath All of This

Here’s something worth sitting with for a moment.

Import markings exist because governments reasonably want to trace weapons that move through commerce. That’s a legitimate goal. The tension collectors feel isn’t with that goal; it’s with the gap between regulatory necessity and the preservation of historical objects as they actually existed.

A high-condition P38 that survived the entire 20th century without being re-finished, re-stocked, or modified in any way represents something genuinely remarkable. The fact that it must now bear a contemporary American importer’s address to legally enter commerce isn’t an irrational policy, but it is a real cost. It’s a cost paid not in money but in historical integrity.

Collectors aren’t being precious when they care about this. They’re being archivists, in an informal way. The best collections tell complete, authentic stories about firearms as they existed in specific historical contexts. Import markings, by definition, add a chapter that wasn’t in the original story.

The good news is that the collector community’s awareness of this issue has, over time, pushed importers toward better practices. The existence of discreet marking services, the reputational premium that companies like Simpson Ltd enjoy for careful placement, and the price differentials that informed buyers demand for heavily marked guns all create market pressure to address the unavoidable requirement with more care and craftsmanship.

That’s how collector markets tend to work at their best. The people who care most, and know most, shape the standards that everyone else ends up following.

Wrapping Up: Marks, Money, and What Really Matters

Import markings on high-end collectible firearms are, in the end, a negotiation between two legitimate interests. Legal traceability on one side; historical preservation on the other. The law wins the legal question; the markings are going on, one way or another. But collectors get to decide what those markings are worth in the market, and they’ve made their answer clear: placement matters, method matters, and an importer who treats the requirement as an opportunity to demonstrate craft and respect for the object will always command more goodwill than one who treats it as a bureaucratic checkbox.

If you’re buying, know your importers. Look at where and how the marks were applied before you agree to a price. Use the marking to verify provenance claims, not just resent it. And if you ever find a pristine bring-back with documentation, no commercial import marks, and a story that actually checks out? Hold onto it. That combination doesn’t come around often.

The stamp on the barrel is just metal and law. The history the gun carries is something else entirely.

Frequently Asked Questions

Not always, placement and visibility are what really drive the impact. A discreet mark inside a magazine well often has little effect on price, while a large, conspicuous stamp on an exposed surface is a different story entirely.

The ATF requires the importer’s name, city, state, and the country of origin on every commercially imported firearm. Since 2002, markings also need to meet minimum depth and size standards so they can’t be easily removed or obscured.

Not necessarily, it could simply mean the firearm entered the U.S. before the Gun Control Act of 1968, when today’s marking requirements didn’t yet exist. Documentation is what actually confirms bring-back status, not the absence of a stamp alone.

Simpson Ltd and Edelweiss Arms have strong reputations in the collector community for placing marks in low-visibility locations, like under the barrel or inside the mag well. Guns imported by houses that take placement seriously routinely command better prices than identical models that weren’t given the same care.

To a trained eye, yes, laser etching and dot-matrix pinning look visually different from the roll markings original manufacturers used, and that difference is noticeable under close inspection. It doesn’t affect legality, but it does affect how integrated the marking looks on a historically significant firearm.

One Response

Good article! Timing couldn’t have been better. I was just explaining this to a young man just entering the collectible firearms market. I am sharing this with him!