Key Takeaways:

- Paper Trumps Metal Every Time: Here’s the reality: without solid documentation, that experimental Colt is just an interesting paperweight with a questionable price tag. Factory letters from archives like Colt or Smith & Wesson run anywhere from $75 to $300+, depending on what you need researched, but they’re worth every penny. You’ll also want auction records, prior appraisals, and a clear chain of custody. Think of it this way: the gun might be 100 years old, but the story still needs to be airtight. No documentation? Walk away, no matter how beautiful that prototype looks.

- Your Eyes Aren’t Good Enough (And Neither Are Mine): I don’t care if you’ve been collecting for 30 years. When you’re looking at a five-figure prototype purchase, professional authentication isn’t optional. Specialized appraisers who focus on your specific manufacturer and era have seen things you haven’t. They know the fakes. They understand period-correct manufacturing techniques. Major auction houses can provide evaluations for consignment or opinions of value that create a paper trail for future sales. Yes, it costs money upfront. It’s still cheaper than discovering you bought a $50,000 fake.

- Legal Compliance Isn’t Boring, It’s Critical: Getting the legal stuff wrong can turn your investment into criminal liability. A C&R license helps with interstate transfers for guns 50+ years old, but shipping rules vary between long guns and handguns – and those rules are changing as courts litigate USPS restrictions. NFA items stay NFA items regardless of “prototype” status, and post-1986 machine guns aren’t transferable to civilians even if they’re experimental. State laws add another layer of complexity. Verify everything before money changes hands, because ignorance won’t protect you if you accidentally violate federal or state firearms laws.

Let’s get started…

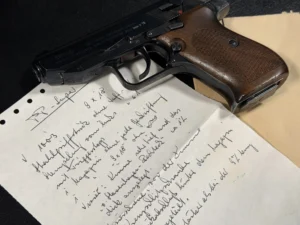

There’s something undeniably thrilling about holding a firearm that was never meant to exist beyond the factory test bench. Prototype guns carry a mystique that production models simply can’t match – they’re the might-have-beens, the evolutionary dead ends, the glimpses into design decisions that shaped firearms history.

But here’s the thing: buying a prototype from a private collection is nothing like picking up a standard Colt 1911 or a Winchester 94. You’re not just purchasing a firearm. You’re buying a story, and stories can be expensive when they turn out to be fiction.

I’ve watched collectors drop serious money on what they thought were genuine prototypes, only to discover they’d bought cleverly modified production guns or outright fakes. The heartbreak is real, and so is the financial hit. So let’s talk about how to protect yourself when you’re eyeing that experimental Smith & Wesson or that one-of-a-kind military trial rifle.

What Are We Actually Talking About?

Before we go further, let’s clarify the terminology. Collectors argue about these words, but here’s how I’m using them:

Prototype – An early experimental version built to test a design concept. Might be hand-made, might be rough.

Toolroom gun – Built in the factory’s tool and die department, often hand-fitted, for testing or demonstration purposes.

Pre-production – Made using production tooling, but before full manufacturing begins. Closer to the final product.

Experimental – Catch-all term for guns made to test modifications, new features, or alternatives to existing designs.

These lines blur constantly. A gun might start as a prototype, get refined in the toolroom, and end up as a pre-production sample. For our purposes, what matters is that none of these were intended for regular commercial sale.

Why Prototypes Command Different Rules

Standard firearms have a predictable value proposition. You can look up production numbers, reference Blue Book values, and compare condition grades with some confidence. Prototypes? They exist in their own universe.

Think about it this way: when a manufacturer produces tens of thousands of a particular model, each one is valuable but replaceable. When they make just a handful of experimental prototypes testing a new design, each of those guns is irreplaceable. That’s where the money is, but it’s also where the risk lives.

The collector market in 2026 has gotten increasingly sophisticated, which cuts both ways. On one hand, we have better authentication tools and more accessible manufacturer archives than ever before. On the other hand, counterfeiters have gotten pretty good at their craft, too.

The Paper Trail Matters More Than the Gun Itself

I know that sounds backwards. You’re thinking, “Shouldn’t I focus on the gun in my hands?” Sure, but without documentation, that gun is just an interesting conversation piece with a murky value.

Factory letters are your best friend. Period. These official documents from manufacturer archives are as close as you’ll get to a birth certificate for your potential purchase. Companies like Colt Archive Properties and the Smith & Wesson Historical Foundation maintain records going back over a century.

The cost varies pretty significantly depending on the manufacturer, model, and type of research required. Smith & Wesson letters typically run around $100 (or $90 for Historical Foundation members). Colt’s pricing is tiered – basic letters might be $75 to $100, but detailed research on older or unusual guns can push into the $200 to $300+ range, depending on what you’re requesting. For complex research or rare models, expect higher costs. Budget accordingly, and check the specific manufacturer’s current pricing before you order.

For often a few hundred dollars, sometimes more depending on maker, model, and research depth, you can get a letter that confirms when your gun shipped, what configuration it had, and critically for prototypes, whether it carried any special designations.

Here’s where it gets tricky, though. Depending on the maker and era, you might see terms indicating experimental status, but these aren’t universal.

Collectors sometimes cite X and T prefixes on Smith & Wesson guns as experimental or toolroom indicators in certain periods, but that’s not a blanket rule. Other manufacturers used different systems, and the coding changed over time. Don’t assume a single letter or prefix means the same thing across all brands or decades.

You might encounter non-standard serial patterns – prefixes, suffixes, or even guns with no serial numbers at all if they were built before serialization requirements. The key is verifying whatever you find through the manufacturer’s archives or with specialists who know that specific maker’s conventions.

But factory letters only go so far. Many prototypes were never officially documented, especially if they didn’t make it past initial testing. That’s where the chain of custody becomes your secondary evidence.

Minimum Documentation You Should Request

Every gun changes hands, and each transaction should leave traces. Here’s what you should ask for at minimum:

- Factory letter (if available for that manufacturer/era)

- Prior auction listings with catalog descriptions

- Previous appraisals from recognized experts

- High-quality photos of all markings, serial numbers, and proof marks

- Written provenance statement from the seller detailing ownership history

- Original sales receipts or transfer documents (if they exist)

- Any period documentation (magazine articles, military reports, designer notes)

Original sales receipts are gold. Auction records from reputable houses like Rock Island Auction Company, Morphy Auctions, or James D. Julia carry weight because these organizations do their homework before listings. Notarized letters from previous owners explaining how they acquired the piece and what they know about its history can fill gaps in the documentary record.

Here’s something collectors sometimes overlook: historical documentation beyond the gun itself. Did a firearms magazine write about this prototype in 1954? Was it mentioned in military trial reports? Do designer notes exist that reference this specific serial number? These contextual documents can validate a prototype’s story in ways that mere examination of the gun never could.

Let me give you an example. A few years back, I heard about a collector who bought what was supposedly an experimental Remington Model 8 variant with a modified gas system. The seller had a good story – grandfather worked in the Remington factory, brought this home as a retirement gift, whole family narrative. Sounded legitimate.

But when the buyer requested a factory letter, Remington had no record of that serial number existing. Turns out it was a post-war modification done by a talented gunsmith, not a factory prototype. Still a neat gun, but worth maybe a tenth of what he paid.

Getting Your Hands Dirty (Literally)

Once you’ve got documentation sorted – or at least know what documentation should exist – it’s time for the physical inspection. This is where you need to channel your inner detective.

Prototypes are weird. That’s kind of their defining characteristic. They often lack the fit and finish of production guns because they were built by hand in experimental departments. You might see tool marks that would never make it past quality control on a standard production line. That’s actually a good sign, not a red flag.

What you’re looking for is consistency. The gun should tell the same story from every angle.

Your Physical Inspection Checklist

Step 1: Markings and Serial Numbers

Production firearms follow predictable marking patterns: manufacturers place proof marks, model numbers, and serial numbers in specific locations using standardized fonts and depths. Prototypes break these rules. You might find hand-stamped numbers that look irregular. Serial numbers might be in odd locations. Some prototypes have no serial numbers at all, especially if they predated serialization requirements or were built before the Gun Control Act of 1968.

Take detailed photos of every marking. Cross-reference whatever numbers you find with manufacturer records when possible. But understand that absence of records doesn’t necessarily mean fake – it might just mean the gun was so experimental it never made it into official documentation.

Be careful with simple letter codes, though. Winchester collectors sometimes see “X” before serial numbers, but that marking can indicate different things depending on the model and era – sometimes it’s experimental, sometimes it’s related to duplicate serial number issues or other manufacturing quirks. Single-letter cues aren’t definitive without tying them to the specific model, period, and verifying through resources like the Cody Firearms Museum records.

Step 2: Parts Originality

Every component should be period-correct and, ideally, original to the gun. This is harder to verify than you’d think. Screws get replaced. Springs wear out. Someone along the line might have swapped a broken part with one from another gun.

For standard production guns, replacement parts are annoying but manageable. For prototypes, they can crater the value. Why? Because you’re not just buying a functional firearm – you’re buying an artifact that documents a specific moment in firearms development history. That original prototype spring might look identical to a replacement spring, but one tells the real story, and one doesn’t.

Look for consistency in manufacturing techniques across all parts. If the receiver shows hand-fitting but all the small parts look machine-perfect from modern production, that’s a red flag.

Step 3: Finish and Patina Consistency

A gun that’s supposedly from 1918 should show age consistent with 108 years of existence. The metal should have a certain character – not necessarily rust or pitting, but a quality that comes from decades of oxidation and handling. The wood should show grain raising, minor dings, and maybe some color changes from hand oils over the years.

What worries me is seeing perfectly matched aging across all components. Even if a prototype sat in a collection unfired for 50 years, different materials age at different rates. Steel doesn’t patina the same way wood does. If every surface looks like it aged at exactly the same rate, someone probably applied artificial aging techniques.

Step 4: Evidence of Manufacturing Methods

Check for tool marks that match the era. Early 20th-century machining left different signatures than modern CNC work. File marks, milling patterns, and hand-fitting evidence – these should all be consistent with the supposed manufacturing period and methods.

You know what’s funny? Sometimes the “flaws” are the most valuable parts. I’ve seen prototype military rifles with sights that were obviously hand-fitted and slightly asymmetrical. A restorer would want to fix that. A serious collector knows that asymmetry is proof of hand construction and increases value.

Green Flags vs. Red Flags

Green Flags (Good Signs)

- Hand-stamped markings with slight irregularities

- Tool marks consistent with period manufacturing

- Natural, inconsistent patina across different materials

- Period-correct screws and small parts

- Documentation from reputable prior owners or auction houses

- Parts that show age-appropriate wear patterns

- Design features that align with known developmental history

Red Flags (Warning Signs)

- Perfect, uniform aging across all surfaces

- Modern machining marks on supposedly old parts

- Serial numbers in the wrong fonts or locations for the manufacturer

- A mix of obviously old and obviously new components

- Seller is reluctant to provide documentation or allow expert inspection

- A story that sounds too perfect or convenient

- A price that seems way too good for what’s claimed

When to Call in the Experts

Look, you might be knowledgeable about firearms. You might even specialize in a particular manufacturer or era. But for five-figure prototypes, assume you’ll need outside eyes. Professional vetting isn’t optional. It’s insurance.

Specialized firearms appraisers exist precisely for this reason. Not just any appraiser – you want someone who specializes in your specific area of interest. If you’re buying an experimental military rifle, find an appraiser who focuses on military firearms. If it’s an early semi-automatic pistol prototype, work with someone who knows that specific manufacturer’s developmental history.

These folks have seen hundreds or thousands of guns. They know what right and wrong look like. They’ve probably encountered the common fakes in your collecting area. They understand metallurgy, manufacturing techniques, and historical context that takes years to develop.

Major auction houses like Rock Island, Morphy, and James D. Julia may provide evaluation for consignment or opinions of value, even for guns they’re not currently selling. The exact services vary, but these specialists routinely conduct evaluations. Yes, it costs money. It’s still cheaper than buying a fake.

Third-party professional evaluation serves another purpose too: it creates a paper trail for future sales. When you eventually sell this gun (and most collectors do eventually), having professional authentication from recognized experts adds value and buyer confidence.

I’d also suggest connecting with collector communities focused on your area of interest. Online forums, collector clubs, and specialist groups often have members who’ve seen similar pieces and can offer insights. The Colt Collectors Association, the Smith & Wesson Collectors Association, Winchester Arms Collectors Association – these organizations exist because knowledge sharing protects everyone from fraud.

But be smart about it. Don’t just post photos on a public forum asking, “Is this real?” That’s how fakers learn to improve their work. Instead, build relationships with established collectors, request private consultations, and share information carefully.

Legal Stuff You Can’t Ignore

Prototypes can create interesting legal situations. Most were never commercially produced, so they might not fit neatly into standard firearms classifications. Getting the legalities wrong doesn’t just affect value – it can turn your investment into a serious legal problem.

A Type 03 Curio & Relic (C&R) FFL can let you acquire qualifying C&R firearms directly across state lines as a licensed collector. The license costs $30 for three years, and the application process is straightforward. But the firearm must actually qualify as C&R – commonly this means 50+ years old and in original configuration, or otherwise officially recognized as C&R by the ATF.

Shipping rules still matter even with a C&R license. The ATF allows shipment to a licensee in any state, but USPS and carrier requirements differ – especially for handguns versus long guns. Generally, non-licensees can mail long guns to a licensee, but handgun mailing through USPS is restricted (typically, licensees only). Private carriers have their own policies, too. These rules are also subject to change – USPS handgun mailing restrictions are currently being litigated in the courts – so confirm current policies with your carrier before attempting to ship.

And state and local laws can be stricter than federal rules. Make sure you understand your jurisdiction’s regulations around firearms transfers.

Here’s something that trips people up: even with a C&R license, you need to verify that the specific firearm qualifies. Some prototypes, particularly those of military designs that were regulated under the National Firearms Act, might require additional paperwork, such as tax stamps. An experimental Thompson submachine gun variant, for example, would still be an NFA item even if it predates commercial production.

For machine guns specifically, remember that only those registered before May 1986 are transferable to civilians. If your prototype is a post-1986 machine gun, it’s not legally transferable to you unless you’re a dealer or manufacturer with the appropriate SOT. This trips up collectors who assume “prototype” or “pre-production” somehow exempts a gun from NFA rules. It doesn’t.

State laws vary wildly. California has different rules from Texas. New York has different rules from Montana. Make sure you understand your state’s regulations around firearms transfers, especially for unusual pieces that might not fit standard definitions.

Safety Isn’t Negotiable

This should be obvious, but prototypes were experimental. That means they weren’t necessarily perfected. Some were abandoned because they didn’t work. Others were potentially dangerous.

Before you even think about loading and firing a prototype gun, have a qualified gunsmith inspect it thoroughly. Check the bore for pitting or erosion. Examine the chamber for cracks. Test the action for proper function. Verify that all safety mechanisms work correctly.

Many prototypes were built before modern metallurgy and heat treatment techniques were perfected. The steel might not be as strong as modern alloys. Design flaws that were discovered during testing might not be immediately obvious to you.

Honestly, most serious collectors of prototypes never fire them. The historical value and the risk to an irreplaceable piece outweigh the enjoyment of shooting. But if you do choose to shoot, start with light loads, use appropriate eye and hearing protection, and maybe do the first few shots with the gun in a sled or rest rather than hand-held.

If You Do Only Five Things

Let me boil this down for you:

- Get a factory letter if possible – Even if records are incomplete, try. Budget accordingly based on the manufacturer and complexity of the research.

- Hire a specialist appraiser – For anything over $5,000, this isn’t optional. Find someone who specializes in your specific manufacturer and era.

- Document everything – Photos of every marking, written provenance, auction records, and previous appraisals. Paper beats the gun.

- Verify legal compliance – C&R eligibility, NFA status, state laws. Get this wrong, and your investment becomes a legal problem.

- Have a gunsmith safety inspection – Before you handle it extensively, and definitely before you fire it. Prototypes can have hidden flaws.

Bringing It All Together

Buying a prototype firearm from a private collection is part treasure hunt, part detective work, and part gamble. The upside is real: you may acquire a truly unique piece of firearms history. The downside is just as real: you can badly overpay for something that isn’t what it claims to be.

Your best protection is thoroughness. Get documentation, verify details, inspect carefully, consult experts, know the law, and prioritize safety.

The firearms-collecting community generally polices itself because serious collectors don’t want fakes in circulation; they hurt everyone. Build relationships with reputable collectors and dealers, learn from them, and ask questions.

The costliest mistakes happen when enthusiasm outruns caution. A prototype may feel like the missing piece in your collection, but it will still be there after another month of proper vetting. Real pieces stay real. Fakes eventually surface.

If you’re new, start small. Buy well-documented examples from trusted sources and build your knowledge before chasing truly rare items. Learn what authenticity looks like by handling confirmed originals.

Many of the best prototype buys go to patient collectors who let opportunities find them rather than chase every intriguing piece. The market is small, and serious items usually move within known collector and dealer networks. Once you’re known as a serious buyer with cash ready, you’ll see pieces before they reach public auction.

This isn’t a hobby for the impulsive or impatient. But if you love engineering history and the story of firearms development, prototype collecting offers rewards that standard production guns can’t match, provided you’re buying the real story, not an expensive piece of fiction.

Frequently Asked Questions

No. Value depends on documentation, originality, and historical significance, not just the word “prototype.”

No. Many prototypes were never formally recorded, but a letter is still the first step in due diligence.

Not necessarily. Some early or experimental guns predate serialization requirements, but the absence must be explainable and supported by context.

Not always. Toolroom guns are often refined and hand-fitted, while prototypes may be rough experimental builds.

Yes, if it is 50 years or older and remains in its original configuration, or if it is otherwise recognized by the ATF.

No. State and local laws can be stricter than federal rules and must always be followed.

Most collectors don’t. If you do, a professional gunsmith inspection is essential, and light loads are strongly advised.