Key takeaways:

- Words Matter More Than You Think: Legitimate factory documentation doesn’t use wishy-washy language like “probably” or “in the style of.” If you’re seeing vague phrasing instead of concrete facts, that’s your first clue something’s off. Real archive letters are boring and specific because they’re pulled straight from manufacturing logs – they tell you exactly what left the factory, not what might have.

- No Serial Number? No Deal: Here’s a simple rule that’ll save you thousands: authentic documentation always references the gun’s serial number. It’s the only way to tie specific paperwork to a specific firearm. Without it, that fancy-looking letter could describe any one of hundreds of guns made during that production run. Don’t let excitement override this basic checkpoint.

- Family Stories Need Backup: “Grandpa carried this at Gettysburg” might be true, and honestly, those stories are what make collecting meaningful. But they’re starting points, not proof. Before you pay premium prices based on oral history, you need supporting evidence – period photos, military records, contemporary correspondence. Great stories deserve real documentation to back them up.

Let’s get started…

You know that feeling you get when you’re looking at a deal that seems too good to be true? Maybe it’s a Civil War-era Colt that comes with a story about a general carrying it through battle, or perhaps it’s a Winchester that supposedly belonged to a famous lawman. The price is reasonable, the seller seems genuine, and the gun looks authentic. But there’s this nagging voice in the back of your head saying, “Wait a minute…”

That voice? Listen to it.

After twenty-plus years in the firearms collecting world, I’ve learned that documentation can make or break a rare gun’s value. We’re talking thousands, sometimes tens of thousands of dollars, hanging in the balance on whether those papers are legitimate or not. The problem is, forged documentation has gotten scarily good. Gone are the days when you could spot a fake from across the room because someone printed it on modern copy paper.

Today’s forgers understand aging techniques; they know what period letterheads looked like, and honestly, they’re counting on your excitement to override your skepticism. So let’s talk about the warning signs that should make you pump the brakes, no matter how badly you want that piece for your collection.

The Language Game: When Words Don’t Add Up

Here’s something I learned the hard way early in my collecting journey. I was looking at what was supposedly a factory-documented Smith & Wesson revolver from the 1890s. The paperwork looked old, felt authentic, and even had that musty smell you’d expect. But when I actually read the language, something felt wrong.

The document continued using phrases such as “in the style of,” “most likely manufactured around,” and “probably configured for.” Look, if you’re paying for factory documentation, you shouldn’t be getting maybes and probablies. Legitimate factory records are boring and specific because they’re literally transcribed from manufacturing logs. They’ll tell you exactly when a gun was made, what configuration it left the factory in, and who it was shipped to.

Vague language is the forger’s best friend. Why? Because it gives them wiggle room. If the gun doesn’t perfectly match the documentation, well, they said “probably,” right? They hedged their bets. Real factory letters don’t hedge. They state facts.

I’ve seen documents that say things like “consistent with production during this period” or “bears features typical of guns from this era.” That’s not documentation, that’s educated guessing dressed up in fancy language. And you’re not paying for educated guesses.

The Timeline Problem: When History Gets Fuzzy

Let’s talk about timing for a second. Say you’re looking at a firearm with historical significance, perhaps connected to a specific battle or a famous figure. The gun supposedly saw action in 1876. Great. Now look at when the documentation was created. Is it from 1876? From the 1880s, when the owner might have written about their experiences?

Or is it from 2005?

This happens more often than you’d think. Someone inherits Grandpa’s old Remington, hears family stories about it, and decades later decides to create “documentation” based on those stories. Sometimes they’re not even trying to deceive anyone; they’re just trying to preserve family history. But here’s the thing: that’s not provenance, that’s genealogy.

Contemporary documentation carries weight because it was created when the events were actually happening. A soldier’s letter home mentioning his service revolver, a period photograph showing the gun, military records that list issued firearms by serial number – that’s the gold standard. Documents created generations later? They’re interesting, sure, but they shouldn’t command a premium price.

I remember examining a Colt revolver that came with a beautifully detailed affidavit from the 1980s describing how the gun was used in the Indian Wars. The affidavit was notarized, professional-looking, and completely worthless for authentication purposes. It was just someone’s family story, written down eighty years after the fact with no supporting evidence.

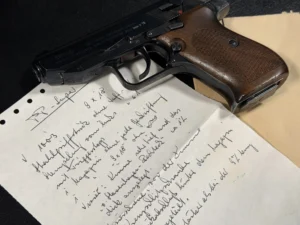

The Serial Number Situation: Your Gun’s Fingerprint

This one drives me crazy because it’s so obvious once you know to look for it. You’re reviewing documentation for a rare firearm, and nowhere, absolutely nowhere, does it mention the gun’s serial number.

Think about that for a minute. Serial numbers are how manufacturers track individual firearms. They’re unique identifiers, like fingerprints. If someone’s authenticating a specific gun, they should be referencing its specific serial number. Otherwise, how do you know the documentation actually corresponds to the gun you’re holding?

I’ve seen factory letters that describe a gun’s configuration in perfect detail – barrel length, finish, grip style, everything – but fail to mention the serial number. That’s a massive red flag. It suggests the letter might be generic, or worse, that it’s describing a different gun entirely.

Here’s what happens: someone gets a generic factory letter for a particular model and year, then tries to pass it off as documentation for a specific gun. Without the serial number to tie them together, the letter could apply to hundreds or thousands of guns made during that production run.

The Colt Archive Properties, Smith & Wesson Historical Foundation, and other legitimate archival services always, always include the serial number in their letters. It’s the first thing they verify. No serial number? Walk away.

Family Stories: Great Yarns, Questionable Proof

Let me be clear about something right up front: I love a good gun story. The tales of how firearms passed through history, the hands they’ve been in, the events they’ve witnessed – that’s what makes collecting romantic and meaningful. But romance doesn’t equal authentication.

“Grandpa carried this at Gettysburg” is a powerful statement. It’s evocative. It connects you to history in a visceral way. It’s also completely unverifiable without supporting documentation.

Family lore is a starting point, not an endpoint. It’s what makes you want to investigate further, to find actual proof. Maybe Grandpa really did carry that gun at Gettysburg. Wouldn’t it be amazing to prove it? That’s when you dig into military records, look for period photographs, search for correspondence that mentions the firearm.

But here’s what I’ve seen too many times: collectors treating oral history as if it were a documented fact. They’ll pay premium prices based on stories alone, then wonder why other collectors and dealers don’t value the gun the same way. The answer? Because stories aren’t transferable proof.

Think of it like this. If I told you I once met a famous actor and they gave me a signed photograph, you might believe me. But if I tried to sell you that photograph for thousands of dollars based solely on my story, you’d want more proof, right? Maybe you’d want to see a video of the signing, or have the signature verified by an expert. The same principle applies here.

Use family stories as inspiration to find real documentation. And when you can’t find it? Be honest about what you have – a great gun with an interesting story, but not proven provenance.

Paper Tells Tales: Physical Document Red Flags

Modern forgers have gotten pretty sophisticated, but paper and ink can still give them away if you know what to look for. I’m not talking about obvious stuff like using computer fonts on supposedly 19th-century documents. I’m talking about subtle anachronisms that require a closer look.

Check the letterhead carefully. Does it match examples from the claimed time period? Companies changed their logos, addresses, and formats over the years. A document supposedly from 1920 using a letterhead design that didn’t exist until 1945 is a problem. Research what the company’s correspondence looked like during the relevant era.

Dates can be tricky, too. Look for inconsistencies. Maybe the document is dated “January 15th, 1889” but references an event that happened in March of that year. Or the document uses dating conventions that weren’t standard for that time and place. These little details matter.

And then there’s the paper’s aging. Real aging happens gradually and consistently. It doesn’t look like someone dunked a document in tea, which creates an unnatural, uniform discoloration. Genuine period paper shows foxing (those brown spots), edge wear, and discoloration that follows logical patterns based on how the document was stored.

For high-value pieces, consider this: many factories and archives will re-verify existing letters for a small fee. Colt, for instance, can check their records to confirm whether they actually issued a specific archive letter. It’s an extra step, but when you’re about to drop serious money, that peace of mind is worth the modest cost.

When the Gun Doesn’t Match the Paperwork

So you’ve got documentation that passes the initial smell test. Great! Now comes the critical part: does the gun actually match what the paperwork describes?

Configuration mismatches are probably the most common issue I see. The factory letter says the gun left the factory with a 4-inch barrel in blue finish with walnut grips. The gun you’re holding has a 6-inch barrel, nickel finish, and rosewood grips. What happened?

Maybe it was modified by the original owner. Perhaps parts were replaced over the years. Or maybe someone’s trying to pass off a different gun using documentation from a more valuable piece. Whatever the cause, those mismatches dramatically affect its value.

Here’s the thing about rare firearms: originality is everything. A gun in original factory configuration is worth substantially more than one that’s been modified, even if those modifications were done period-correct. Documentation describing a gun that no longer exists in that form isn’t worth much.

I always tell new collectors to examine every detail mentioned in the documentation and verify that it matches the physical gun. Barrel length, finish type, sight configuration, grip material, any special markings or engravings – it should all line up perfectly. If it doesn’t, you need a really good explanation before proceeding.

The Wear Pattern Puzzle

Guns age in predictable ways based on use and storage conditions. Wood and metal patina differently. Edges show wear first. High-contact areas develop shine. When you’ve handled enough old firearms, you start to develop an eye for authentic aging versus artificial or inconsistent wear.

A gun that shows heavy oxidation on the metal but has pristine, barely-used wood stocks? That’s suspicious. Either the stocks have been replaced (which should be disclosed), or someone’s trying to hide the true condition through selective restoration.

I remember a Winchester rifle whose metal showed a beautiful, even patina consistent with its claimed age, but the stock looked suspiciously fresh. Turned out the stock had been completely refinished, removing all the dings, dents, and character marks that would’ve accumulated over a century of use. That refinishing cut the value by more than half, but the seller was hoping buyers wouldn’t notice.

Blurred markings are another giveaway. Factory stampings should be crisp and clear, even on old guns. If they look washed out or “dished” – like they’re sitting in shallow depressions – the metal has probably been heavily polished or refinished. People do this to remove pitting or to smooth out areas where they’ve altered markings.

And that brings us to the scariest modification: altered serial numbers.

Serial Number Shenanigans: The Ultimate Fraud

I’m going to be blunt here. If you suspect a serial number has been altered to match a historically significant firearm, stop everything and get expert verification immediately. This isn’t just about money; it could involve legal issues.

Fresh-looking serial numbers on otherwise aged guns are the biggest red flag. Serial numbers should show the same wear and patina as the surrounding metal. If they look crisp and sharp while everything else is worn, someone’s been messing with them.

Sometimes, forgers will over-stamp existing numbers to change them. Other times, they’ll grind down the metal and re-stamp entirely. Under magnification, you can often see tool marks, inconsistent depth, or alignment issues that reveal the fraud.

Why do people do this? Because tying a gun to a famous figure or a significant historical event can exponentially increase its value. A standard Colt Single Action Army might be worth $3,000. That same model, if it can be proven to have belonged to Wyatt Earp? We’re talking hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The temptation to “match” a gun to valuable documentation or historical records has created a whole underground industry of serial number manipulation. Don’t become a victim. If a gun’s provenance seems too incredible, have the serial numbers examined by an expert before you buy.

Your Verification Toolkit: Resources That Actually Help

Alright, so you’re armed with knowledge about red flags. What now? How do you actually verify documentation and provenance? Let me walk you through the resources serious collectors use.

Factory letters are your starting point. For Colts, contact the Colt Archive Properties. They maintain records going back to 1873 and can provide official documentation of what configuration a gun left the factory in. Smith & Wesson has its Historical Foundation, and Ruger maintains archives of its firearms. These letters aren’t free, usually running a couple of hundred dollars, but they’re worth their weight in gold for authentication purposes.

Winchester, Marlin, and L.C. Smith collectors should know about the Cody Firearms Records Office at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. They house extensive factory records and can research the original configuration and shipping destination of many firearms. Again, there’s a fee, but you’re paying for access to primary source documentation.

For broader historical verification, professional appraisers who specialize in antique firearms are invaluable. They’ve seen thousands of guns and their documentation. They know what authentic looks like and what should raise concerns. Yes, you’ll pay for their time, but catching a fake before you buy saves you way more than the appraisal costs.

Major auction houses like Rock Island Auction Company and Morphy Auctions employ their own expert teams to authenticate items. Even if you’re not buying through an auction, watching their sales and reading their catalog descriptions can teach you a lot about what proper documentation looks like.

Putting It All Together: Trust But Verify

When you finally find a rare piece you’ve chased for years, you want to believe the story, the documents, the provenance. That excitement makes collecting fun, but it also makes you vulnerable.

Balance enthusiasm with skepticism. Love the gun, but question its documentation. Check every claim. Verify serial numbers. Look for inconsistencies. Make sure the gun matches the paperwork. Don’t accept vague language or unprovable stories instead of real proof.

Imperfect paperwork doesn’t make a gun worthless. An honest seller might say, “This is a beautiful example of a 1873 Colt, but I can’t verify the family story about its use in the Indian Wars.” That gun still has value, just not the premium that proven provenance brings.

What kills value is misrepresentation. Paying a premium for a gun with shaky documents, only to learn the provenance is unverifiable, leaves you stuck with an overpriced piece.

The collectors who last are the ones with healthy skepticism. They ask hard questions, don’t take stories at face value, and pay for proper authentication before they pay for the gun. They end up with collections they can be proud of, genuine pieces with trustworthy paperwork.

Be one of those collectors. Ask questions. Demand proof. Trust your instincts when something feels off. There will always be another gun and another deal. Digging out from a bad purchase based on fraudulent documentation is far harder.

Your collection deserves more than pretty stories and questionable papers. It deserves the real thing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Most factory archive letters run between $100 and $ 300, depending on the manufacturer and how deep you need them to dig. It’s honestly a small price to pay when you consider it could save you from a multi-thousand-dollar mistake.

Family-held documents are great starting points, but you’ll still want them verified by factory archives or experts. Age alone doesn’t guarantee authenticity – I’ve seen convincing forgeries that were decades old.

Modifications aren’t necessarily deal-breakers, but they need to be disclosed and will significantly affect value. A factory letter describing the original configuration is still useful because it establishes what the gun was before changes were made.

Look for inconsistent wear patterns – the serial number should show the same patina as the surrounding metal. When in doubt, have it examined under magnification by someone who knows what tool marks and re-stamping look like.

Major auction houses like Rock Island and Morphy employ expert teams and stake their reputations on accurate descriptions. They’re generally trustworthy, but you can always request additional verification for high-value pieces.