Key Takeaways:

- Conservation beats restoration every time. Your job isn’t to make that antique firearm look brand new; it’s to stop it from getting worse. Original condition, even if worn, is what serious collectors pay top dollar for. That patina you’re itching to polish away? That’s actually adding value, not hurting it.

- When in doubt, do nothing. This is the hardest rule to follow because every instinct tells you to clean and improve. But with collectible guns, the best action is often no action at all. Active rust spreading? Sure, address it. A bit of dust or natural aging? Leave it alone. You can always clean more later, but you can’t undo damage to original finishes.

- Your bare hands are the enemy. Even freshly washed hands deposit oils and acids that, over time, etch metal and stain wood. Wear cotton or nitrile gloves whenever you handle a collectible firearm. It seems like overkill until you see the difference it makes after just a few years. Museums do this for a reason, and your collection deserves the same care.

Let’s get started…

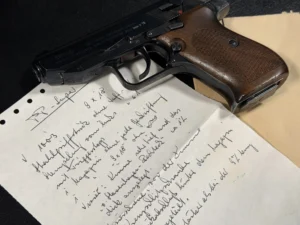

There’s something almost sacred about holding a piece of history in your hands. Maybe it’s a Springfield 1903 that saw action in the trenches, or a Colt Single Action Army from the Wild West era. Whatever it is, that firearm represents a tangible connection to the past, and if you’re not careful, you can destroy that connection with a single well-intentioned cleaning session.

I’ve seen it happen. A collector picks up a beautiful Winchester at an estate sale, sees some surface grime, and thinks, “I’ll just polish this up a bit.” Three hours later, they’ve stripped away a century of patina (that natural aging and tarnish on the metal that serious collectors actually value), obliterated the original finish, and turned a $3,000 piece into an $800 wall-hanger. Collectors consistently pay the most for firearms in original condition; even well-intentioned “improvements” can slash value by 50% or more. It’s heartbreaking, really.

The truth is, maintaining collectible firearms isn’t like keeping your modern hunting rifle in top shape. It requires a completely different approach, one that might feel counterintuitive at first. You know what? That’s exactly what we’re going to tackle here.

The First Rule: When in Doubt, Do Nothing

Before we get into the how-to details, let’s establish the most important principle right upfront: the best default action is often no action at all.

I know that sounds strange. You’re looking at this antique firearm, and it’s got some dust, maybe a bit of discoloration, and every instinct tells you to clean it up. But here’s the thing, with collectible guns, original condition is valued far more than a “shiny” appearance. That worn finish you’re itching to improve? That’s what buyers are looking for. It’s proof that the gun is authentic and hasn’t been messed with.

So before you touch that firearm with anything, ask yourself: Does this actually need intervention? Is there active rust spreading? Grime trapping moisture? Or are you just reacting to the natural appearance of an aged item?

If you’re uncertain about a gun’s historical importance, rarity, or value, consult an expert or appraiser before any cleaning. Some firearms have historical significance that isn’t immediately obvious; maybe it’s a war relic or was owned by a notable figure. Even gentle cleaning of such pieces could significantly reduce their value.

It’s natural to want to clean and improve things. That impulse isn’t wrong; it’s just wrong for this particular hobby. With collectibles, restraint is the name of the game.

Conservation, Not Restoration (There’s a Huge Difference)

Let me be blunt: if you approach antique firearms with a restoration mindset, you’re going to wreck their value. Period.

Here’s the thing most people don’t realize initially. Collectors and serious buyers aren’t looking for firearms that appear brand-new. They want authenticity. They want original finishes, natural aging, and yes, even that patina you might think looks “dirty.” That worn bluing (the dark blue-black finish applied to steel), those honest handling marks, that aged case hardening (a heat-treating process that creates beautiful mottled colors on metal), these aren’t flaws. They’re proof of authenticity and historical integrity.

Conservation means stabilizing what’s already there. You’re preventing further deterioration, not rolling back the clock. Think of yourself as a museum curator, not a car restorer. Even museums like the NRA National Firearms Museum favor conservation, they avoid altering original finishes and instead use gentle preservation methods. Major museums use microcrystalline wax (such as Renaissance Wax) on antique firearms to protect metal and wood, and handlers always wear cotton gloves to avoid leaving fingerprints. Your goal is to stop rust from spreading, prevent wood from cracking, and keep mechanisms from seizing, not to make everything shiny and new again.

Restoration, on the other hand, involves actively changing the firearm’s current state. Rebluing, refinishing stocks, replacing parts, and aggressive polishing all fall under the category of restoration. And while there might be a place for restoration on damaged wall-hangers or shooters, it’s death to collectible value. The editor of Military Trader magazine has noted repeatedly that any refinishing or aggressive cleaning lowers the value of historic firearms.

The collector market has spoken pretty clearly on this. Original condition, even if worn, almost always commands premium prices over restored pieces. There are exceptions, sure, but they’re rare enough that you shouldn’t bet your collection on being one of them.

The Golden Rule: Only Intervene When Absolutely Necessary

If there’s one principle that should guide every move you make with a collectible firearm, it’s this: do no harm.

Seriously, put down that cleaning rod and ask yourself, “Does this actually need to be done?” It’s completely understandable to want to clean it; these are valuable, interesting pieces. But with collectibles, less is genuinely more.

Active rust? Yeah, that needs to be addressed because it’ll keep spreading and causing pitting. Grime that’s trapping moisture? Take care of it. But surface dust? A light patina? Slight discoloration? Leave it alone. These aren’t problems; they’re features.

Think about it this way: every time you touch a collectible gun with a cleaning implement, you’re making an irreversible change. These items are only original once. You can always clean more later if needed, but you can’t unclean something. Once that original finish is gone, it’s gone forever. And trust me, buyers can tell the difference, even subtle overcleaning shows up under close inspection.

One more critical point: avoid unnecessary disassembly. Every time you remove screws or parts, you risk scratches, dents, or marred screw heads that can lower the value. If cleaning internal parts is needed, consider having it done by a qualified gunsmith or an antiques conservator.

Handling the Exterior Metal (Without Killing the Finish)

Alright, so you’ve decided cleaning is actually necessary. What now?

Start gently. I mean, really gentle. Your first move should always be a soft cotton cloth or an Otis microfiber cloth. No chemicals, no pressure, just a light wipe-down to remove surface dust and loose debris. You’d be amazed at how often this is all that’s needed.

Got something more stubborn? Here’s where most people make their first mistake. They reach for gun oil or modern solvents. Don’t. Instead, try warm distilled water. Yep, just water. Dampen your cloth slightly, not dripping wet, and gently wipe the affected area. The keyword here is gently. You’re not scrubbing a barbecue grill.

After using any moisture, even distilled water, dry everything immediately. And I mean immediately. Use a clean, dry cloth and make sure every trace of water is gone. Moisture is the enemy of metal, especially on firearms that might already have compromised finishes.

What about stubborn rust or corrosion? This is where you need to exercise real judgment. Light surface rust might respond to gentle attention with a cloth and mineral spirits (always test on a small, inconspicuous area first). Heavier rust? You might need professional conservation help. The line between removing harmful corrosion and damaging the original finish is razor-thin.

Here’s what you absolutely must avoid: steel wool, sandpaper, wire brushes, or abrasive compounds of any kind. These will destroy patina, remove original finishes, and leave scratches that scream “amateur restoration” to any knowledgeable buyer. Even bronze brushes can be too aggressive for some antique finishes.

Now, professional conservators sometimes use specialized techniques that amateurs should not attempt, such as superfine 0000 steel wool in very controlled circumstances to remove converted rust or specific rust-conversion treatments. These are exceptions under expert hands only. For the rest of us, the safest path is the gentle one.

The Bore Deserves Special Attention

Okay, let’s talk about barrel care, because this is where things get a bit technical, but stick with me, it matters.

The rifling inside an antique barrel is often in surprisingly good shape, even after decades or centuries. But it’s also delicate, especially on older firearms, where the steel might not meet modern standards. Using the wrong cleaning rod can actually damage those rifling lands.

Use a high-quality one-piece cleaning rod, ideally nylon-coated or carbon fiber, with a brass or soft jag. Avoid multi-piece aluminum or brass rods, as they can pick up grit and wear the bore. The goal is to prevent the rod from contacting the rifling during cleaning. Some experts note that a polished, hardened steel one-piece rod with proper guides is acceptable, too, but the key is always protecting the rifling through proper technique and equipment.

And honestly, bore cleaning on collectibles should be minimal anyway. Unless the bore has active rust or really heavy fouling, less is more. A quick pass-through with a clean patch to remove dust and check the condition is often sufficient.

If you do need to clean more thoroughly, avoid harsh ammonia-based bore cleaners on antique firearms. Strong ammonia can etch older steel and strip finishes if misused. Modern smokeless powder solvents are formulated for modern metallurgy. Older steels can react poorly to aggressive chemicals.

For antique bores, use a gentle, classic cleaner like Hoppe’s No. 9. It’s mild but effective for most antique firearms and won’t harm older steel. Stick with proven, gentle options, or better yet, consult with a conservator if you’re dealing with significant bore issues.

Wood Stocks Need Love Too (But Not Too Much)

Wood stock care is where a lot of collectors get themselves into trouble. There’s a persistent myth that old wood needs to be “fed” with oils to prevent it from drying out. Let me save you some heartache: this is mostly nonsense.

Historical wood finishes on firearms were typically varnishes, shellacs, or oils that were already well-cured when the gun was made. These finishes don’t benefit from modern treatments and can actually be harmed by them. Many military antiques were originally finished with oils, such as boiled linseed oil, but once cured, these finishes don’t need routine “conditioning” in most cases.

For routine maintenance:

- Use a slightly damp cloth with just a few drops of mild detergent

- Wipe down the wood gently to remove surface grime, fingerprints, dust, that sort of thing

- Follow up immediately with a dry cloth

- That’s it. Simple, right?

Unless a wooden stock is absolutely desiccated (which is very rare), adding linseed or tung oil will do more harm than good. If you encounter an extremely dry stock, and I mean truly parched, with the wood actually cracking, very lightly applying boiled linseed oil and then wiping it all off might be appropriate. But this is the exception, not the rule, and even then it should be approached with extreme caution.

What about those deep scratches or dings? Leave them. They’re part of the gun’s history. What about that darkened area where someone’s hand rested for decades? Leave it. That’s honest wear. What about, you get the idea.

Here’s what not to do: don’t use linseed oil, tung oil, or modern wood conditioners unless you’re absolutely certain they’re appropriate for that specific firearm. These products can darken wood, alter the appearance of original finishes, and generally make a mess of things. I’ve seen beautiful original stocks turned dark and blotchy because someone thought they were “conditioning” the wood.

Oil-based soaps are another no-go. They can leave residues that attract dust and, over time, potentially affect finishes.

Products That Actually Work (Without the Marketing Hype)

Let’s talk about what you should actually be putting on your collectibles. The gun care market is flooded with products, and frankly, a lot of them are wrong for antique firearms, even if the marketing says otherwise.

Recommended conservation products include:

- Renaissance Wax: A museum-grade microcrystalline wax for both metal and wood. Museums around the world use this stuff because it works. It creates an inert, protective barrier that doesn’t attract dust the way oils do, and it’s completely reversible. Apply sparingly with a soft cloth, let it haze, then buff gently. A little goes a long way.

- CorrosionX for Guns or Break-Free CLP: Light modern gun oils that protect without damaging vintage finishes. They’re formulated to provide protection without the thick buildup of old-school gun oils, and they don’t leave heavy residues. Petroleum-based gun oils without aggressive additives (like Rem Oil or G96) are also safe for antique firearms when used appropriately.

- Mineral spirits: Gentle solvent for degreasing metal parts and removing old, hardened lubricants. Use sparingly and always test on a small, inconspicuous area first. Effective at breaking down old grease and oil without harming most finishes.

- Hoppe’s No. 9: A classic, mild bore cleaner that’s safe for antique bores and won’t harm older steel.

What about all those specialty antique gun care products you see advertised? Some are fine, some are overpriced, and some are actively harmful. Do your research, ask other collectors, and when in doubt, stick with proven museum-grade materials.

Handling and Storage (Because Your Hands Are Gross)

Sorry, but it’s true. Even freshly washed hands deposit oils, acids, and salts onto metal surfaces. These contaminants can etch metal and stain wood over time. On a modern firearm you’re shooting regularly, this isn’t a huge deal. On a collectible you’re preserving for the long term, it adds up.

The solution is simple: wear gloves. Clean white cotton gloves work great and are cheap. Nitrile gloves are another good option, especially if you need better dexterity. Just keep a box of them with your collection and make it a habit. This is exactly what museums do; handlers always wear cotton gloves to avoid fingerprints.

Some collectors think this is overkill. Those collectors are wrong. I’ve seen firsthand the difference in condition between firearms that were always handled with gloves versus those that weren’t. The gloved guns look noticeably better, even after just a few years.

Storage is equally critical. Climate control is non-negotiable if you’re serious about preservation. Aim for 40% to 50% relative humidity and temperatures between 65°F and 70°F. This range prevents both excessive dryness, which can crack wood, and humidity, which can promote rust.

A quality gun safe with humidity control is a worthwhile investment. But here’s a critical point: avoid soft cases for long-term storage. Those foam-lined cases might seem protective, but they trap moisture like crazy. I’ve seen guns develop significant rust in just a few months when stored in soft cases.

Silicone-treated gun socks are better; they wick moisture away rather than trapping it. Use them inside a humidity-controlled safe for best results.

The Mistakes That Keep Happening (Learn From Others’ Pain)

You know what’s frustrating? Seeing the same errors repeated over and over. Let me save you some pain by highlighting the biggest ones:

1. Aggressive over-cleaning. I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating: you cannot scrub, polish, or abrade your way to better value. Every time you think “just a little more,” stop. You’re probably already past the point where you should have stopped.

2. Using harsh modern solvents without understanding their chemistry. That bore cleaner, that’s amazing for your AR-15? Might be too harsh for a 100-year-old shotgun. That stock treatment that works wonders on furniture? Could ruin an original finish.

3. Trying to fix every little flaw. Not everything needs to be fixed. Some wear is desirable, some patina is valuable, and some marks tell the gun’s story.

4. Poor storage with wild temperature or humidity swings. Basements flood. Attics bake. Garages do both. A gun safe in a climate-controlled living space is worth its weight in gold.

5. Failing to document the condition before doing anything. Take detailed photos before you clean or maintain a piece. If something goes wrong, at least you’ll have proof of what it looked like before. And if you’re smart, those photos will make you think twice about whether intervention is really necessary.

When to Call in the Professionals

Here’s a hard truth: there are situations where you need expert help. Knowing when you’re out of your depth is part of being a responsible collector.

Active rust that’s spreading despite your efforts? Conservator time. Mechanical issues that prevent proper function? A gunsmith who specializes in antiques. Mysterious corrosion you can’t identify? Expert evaluation needed. Valuable pieces that need serious intervention? Don’t even think about DIY.

Professional conservation isn’t cheap, but it’s cheaper than ruining a valuable firearm. A good conservator understands the balance between preservation and value. They know when to act and when to leave well enough alone. They have access to tools, materials, and knowledge you probably don’t.

Look for conservators with museum experience or credentials from organizations like the American Institute for Conservation. For mechanical work, seek out gunsmiths who specialize in antique firearms and understand the collectible value of these firearms.

Wrapping This Up

Taking care of collectible firearms is really about changing your mindset. You’re not maintaining these guns the way you’d maintain a modern firearm you shoot every weekend. You’re preserving pieces of history for future generations.

That means restraint. It means accepting honest wear as part of the package. It means understanding that your role is to prevent deterioration, not reverse aging.

Will this approach keep your guns looking impressive? Absolutely. Will they look brand new? No, and that’s exactly the point. They’ll look authentic, well-preserved, and historically significant. And that’s what serious collectors are willing to pay for.

The collectors who understand this principle are the ones whose firearms maintain and increase in value over time. The ones who don’t, well, they learn expensive lessons.

So next time you’re tempted to give that collectible a “good cleaning,” remember: the best action is often no action at all.

And when action is necessary, less is almost always more.

Your collection will thank you, and so will your bank account when it comes time to sell or pass these pieces on.

Frequently Asked Questions

It depends on how you clean it. Aggressive cleaning, polishing, or the use of harsh chemicals can slash value by 50% or more, but gentle conservation using proper methods can actually help preserve value.

Patina is the natural aging and tarnish on metal that collectors value as proof of authenticity. Rust is active corrosion that spreads and causes pitting. Patina is stable; rust keeps eating away at the metal.

Yes, but choose carefully. Petroleum-based oils without aggressive additives (like Break-Free CLP or Rem Oil) are generally safe, but for long-term storage, museum-grade microcrystalline wax like Renaissance Wax is better because it doesn’t attract dust.

Only if absolutely necessary. Every time you remove screws or parts, you risk scratches, marred screw heads, or dents that lower the value. Let a qualified gunsmith handle disassembly if it’s really needed.

Honestly? Way less than you think. If they’re stored properly in a climate-controlled environment, an annual inspection with light dusting might be all they need; overcleaning causes more damage than undercleaning.